Instant Connection for Pixel Streaming

— New Feature Automated Setup

Moving Your Timeline Between NLEs Using XML

Moving Your Timeline Between NLEs Using XML

Moving Your Timeline Between NLEs Using XML

Published on January 9, 2026

Table of Contents

It usually starts with a simple request.

“Can you send the timeline?”

Not a video. Not stems. The actual timeline. And you look at the deadline, glance at your project, and tell yourself the lie we all tell ourselves. This should be easy.

It never is.

The moment XML enters the picture, you stop editing and start translating. Different apps. Different rules. Same timeline, somehow behaving differently the second it leaves home. You export the XML, send it off, and wait for the inevitable follow-up messages.

Cuts a frame off. Clips offline. Audio tracks scrambled. Titles gone.

The edit was fine five minutes ago. Now it’s… not.

XML isn’t a magic handoff. It’s a fragile truce between NLEs. Sometimes it holds. Sometimes it breaks immediately. And if you’ve done this more than once, you already know which side of that coin it usually lands on.

That’s the reality we’re dealing with here.

What XML Actually Is (and What It Isn’t)

Here’s the part people usually misunderstand, even experienced editors.

An XML file doesn’t move your project. It describes it.

Think of XML as a set of instructions. Where clips start and stop. Which files are used. How tracks are stacked. Basic timing, basic structure, basic relationships. That’s it. No media. No renders. No real understanding of creative intent.

This is why XML can feel both powerful and deeply disappointing at the same time.

In my experience, XML is great at one thing: rebuilding the skeleton of a timeline somewhere else. It knows your cuts. It knows your clip order. It usually knows your timecode. If that’s all you need, you’re in decent shape.

The problems start when you expect more than that.

Effects don’t translate cleanly because they aren’t universal. A blur in one NLE isn’t the same blur in another. Titles are often proprietary. Motion settings, keyframes, speed ramps, adjustment layers… all fair game to get ignored or misinterpreted. XML isn’t being lazy. It just doesn’t know what to do with those instructions.

Audio is another trap. Track-based editors and clip-based editors think very differently. XML tries to bridge that gap, but it doesn’t always succeed. You’ll see clips move tracks, automation disappear, or roles collapse into something that technically works but feels wrong.

And no, XML isn’t broken because of this. It’s just limited.

I’ve noticed a lot of frustration comes from treating XML like a project file replacement. It isn’t. It’s closer to a translator that only speaks half the language. Enough to get the point across. Not enough to preserve nuance.

That’s also why XML still matters. As flawed as it is, it’s the closest thing we have to a shared vocabulary between NLEs. When timelines need to move between people, apps, or stages of post, XML is usually the least bad option on the table.

The key is knowing what you’re asking it to carry. Structure, yes. Polish, no. Once you internalize that, the whole workflow gets a lot less frustrating.

Why XML Transfers Break More Often Than People Admit

Most XML failures aren’t dramatic. They’re subtle. And that’s what makes them dangerous.

The timeline opens. Nothing crashes. At first glance, it looks fine. Then you zoom in. A cut is one frame late. An audio clip starts a few milliseconds early. A transition is technically there, but not doing what it was doing before. Individually, these are small problems. Stack enough of them together and your “quick handoff” turns into an hour of cleanup.

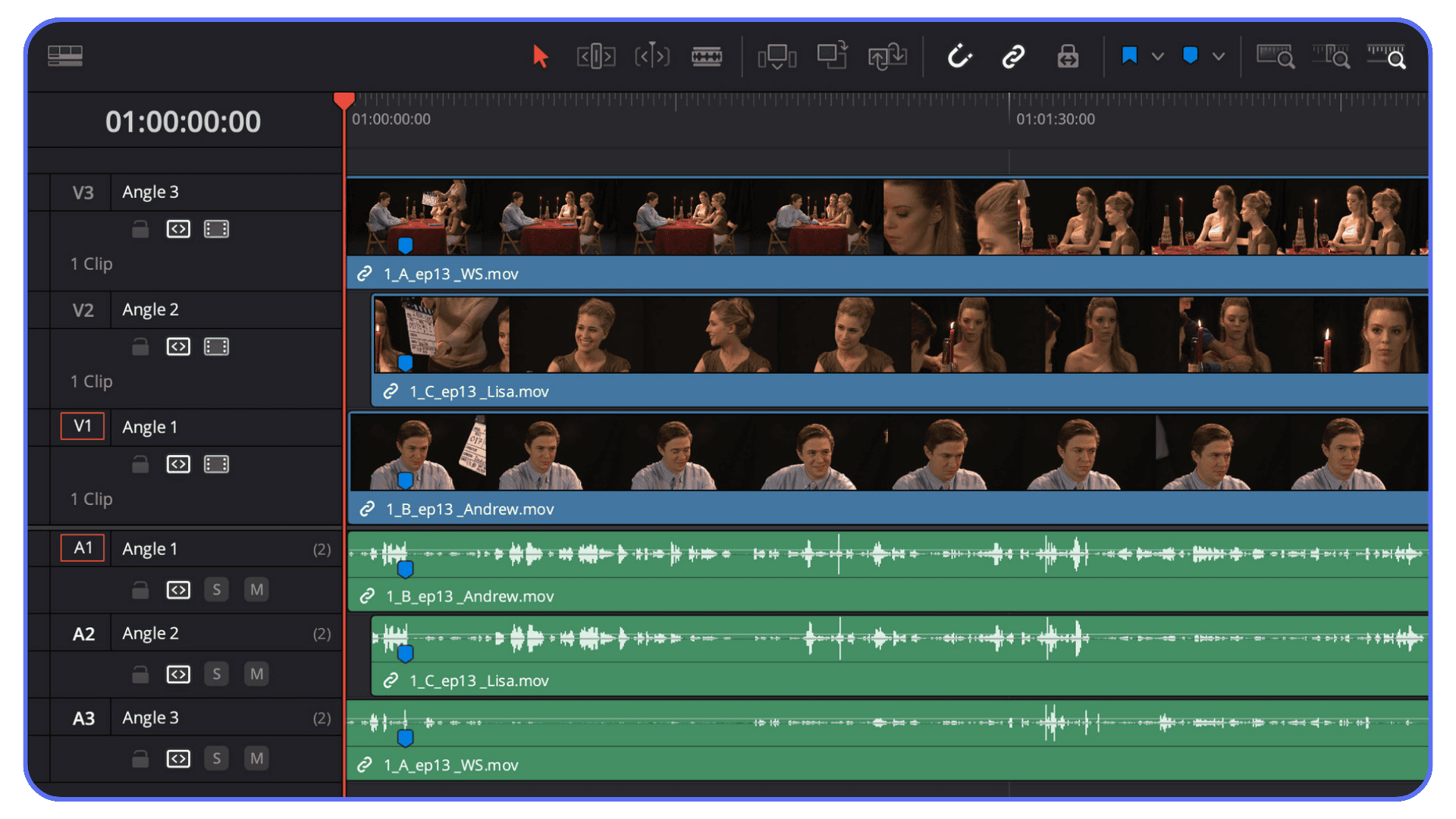

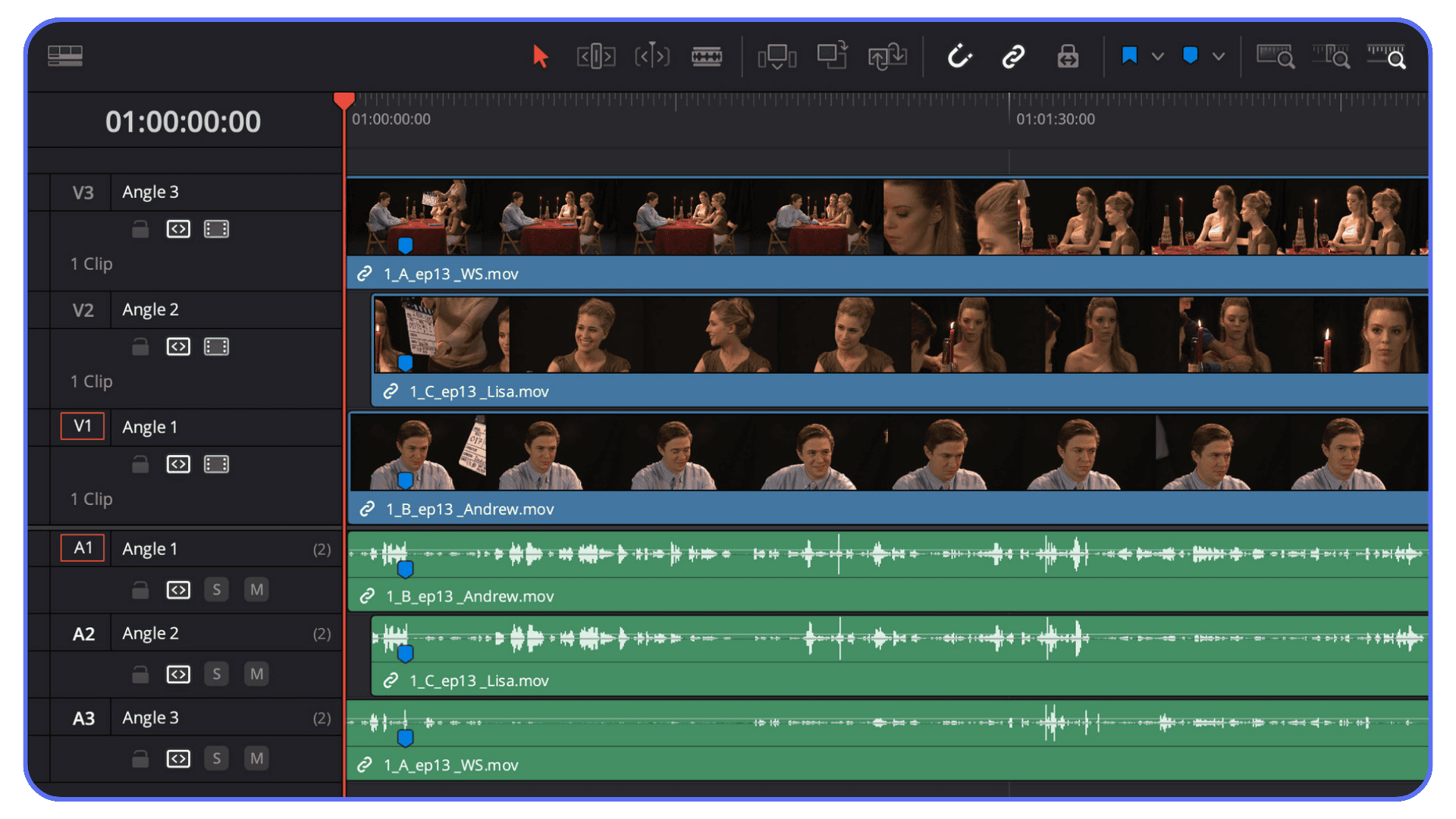

One big reason this happens is that NLEs don’t agree on how timelines should behave. They all cut video, sure, but under the hood they’re wildly opinionated. Track-based vs clip-based. Different assumptions about timecode, sample rates, even what “a frame” means in edge cases.

Effects are the most obvious casualty. If the destination app doesn’t have an equivalent effect, XML just shrugs and moves on. Sometimes you get placeholders. Sometimes you get nothing. Speed changes and retiming are especially fragile. Anything involving keyframes should be treated as guilty until proven innocent.

Multicam is another common failure point. Many XML exports flatten multicam clips into a single angle. The edit stays intact, but the flexibility is gone. That’s fine for finishing. It’s a nightmare if you expected to keep adjusting angles.

Then there’s frame rate drift. This one catches people off guard. The timeline frame rate might technically match, but field order, timebase interpretation, or fractional rates can cause the destination NLE to read the project differently. Suddenly a 25fps timeline behaves like 50. Or audio slowly slips over time. No error message. Just vibes. Bad ones.

Audio routing deserves its own warning label. Roles, submixes, and buses rarely survive intact. XML can move clips, but it struggles to preserve intent. You’ll often end up with audio that’s technically there but logically scrambled.

I think the biggest myth is that XML problems mean someone did something wrong. Most of the time, nobody did. You just crossed a boundary where assumptions stopped lining up.

That’s why experienced editors don’t expect a perfect transfer. They expect a usable starting point. The mistake is believing XML will give you more than that.

Exporting XML From Different NLEs Without Sabotaging Yourself

Most XML disasters don’t happen on import. They happen right here. At export. Quietly.

A lot of editors treat XML export like a final step. Click the menu item, pick a version, send the file. Done. That’s how you end up fixing things later that you could’ve avoided in two minutes up front.

Different NLEs write XML differently, and the choices you make before exporting matter more than the XML version number itself.

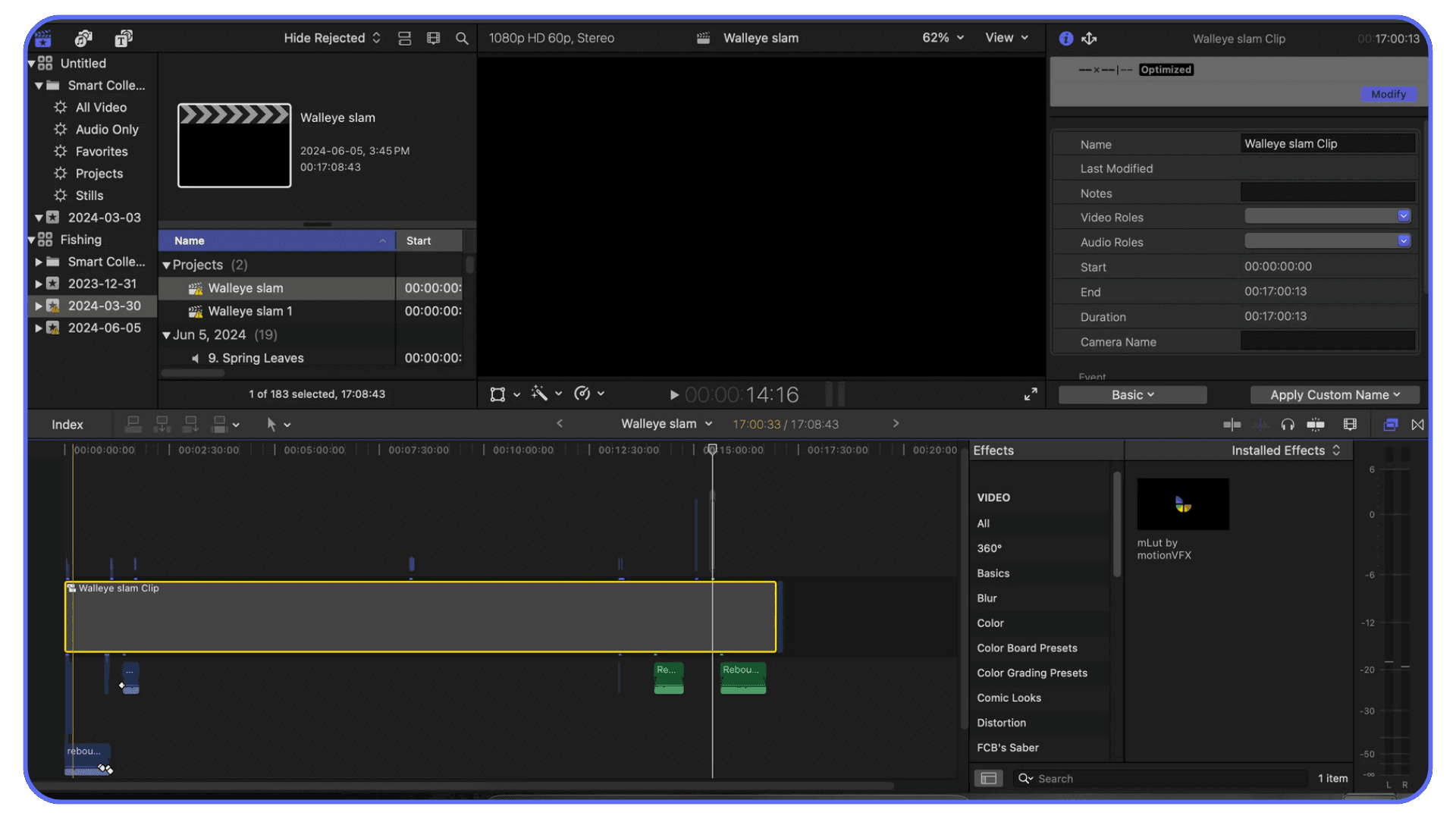

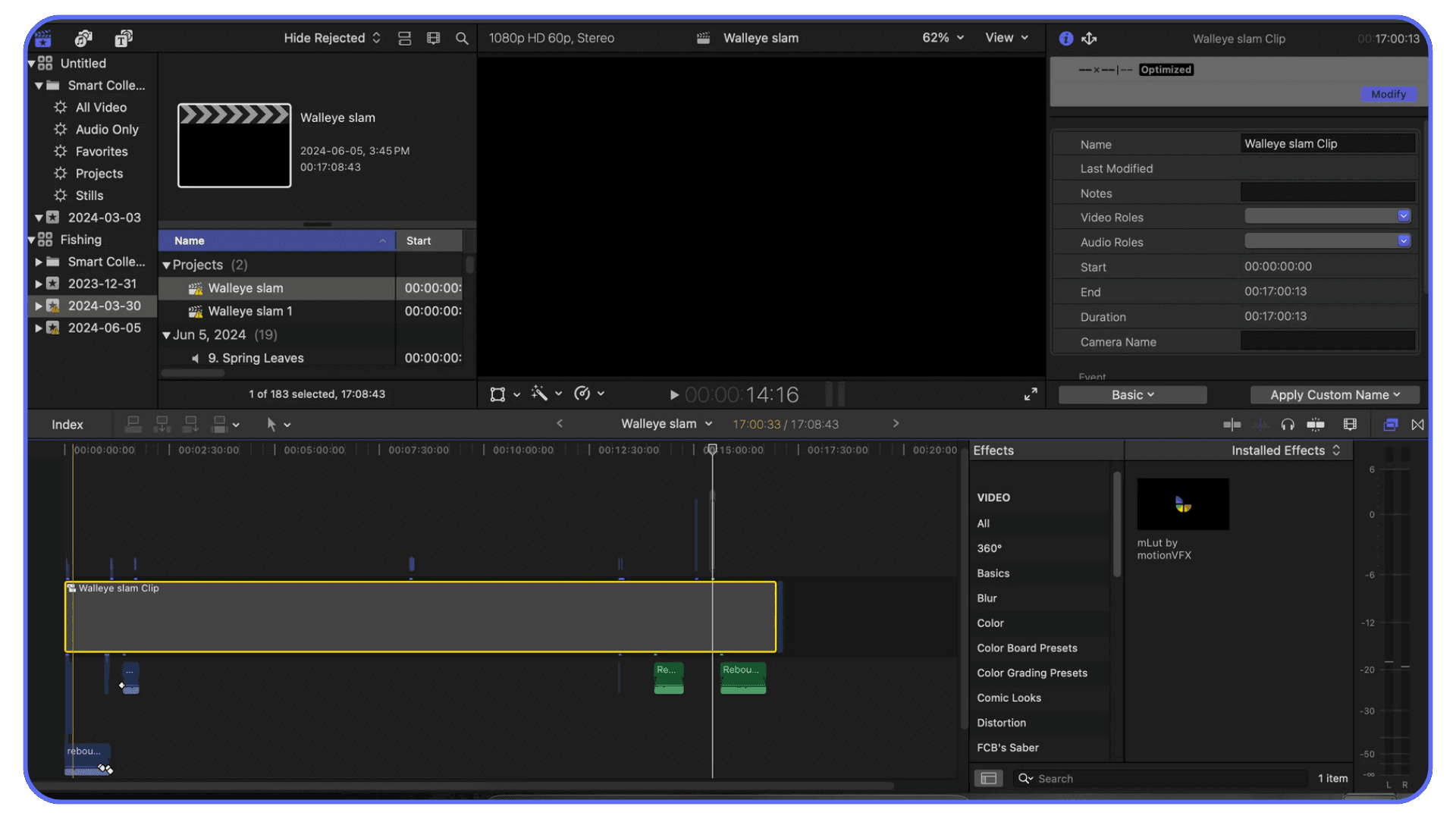

Final Cut Pro

Final Cut’s XML is powerful, but it’s also very literal. It exports exactly what’s in the timeline, including complexity you may have forgotten about.

Compound clips are the first trap. XML will carry them, but not every app knows what to do with them. If the timeline is leaving Final Cut, flatten compounds unless you have a very good reason not to. Same goes for multicam. If the receiving editor doesn’t need angle control, flatten it. You’re trading flexibility for predictability, and predictability wins most of the time.

Roles are another gotcha. They’re great inside Final Cut. Outside of it, they often collapse into basic tracks. Before exporting, clean them up. Fewer roles. Clear intent.

And always export the newest XML version supported by the destination app. Newer versions usually behave better, but only if the other side can read them properly.

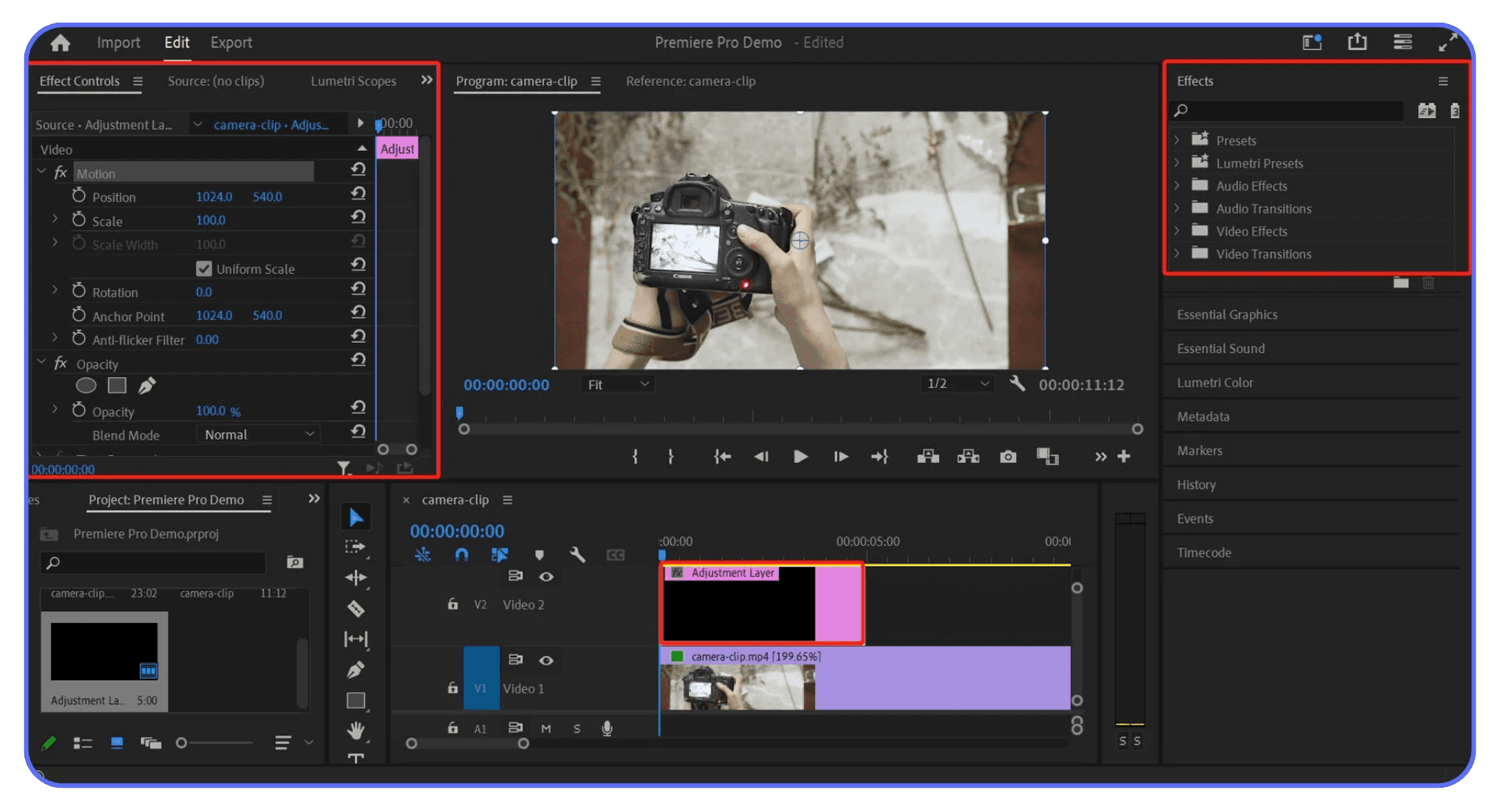

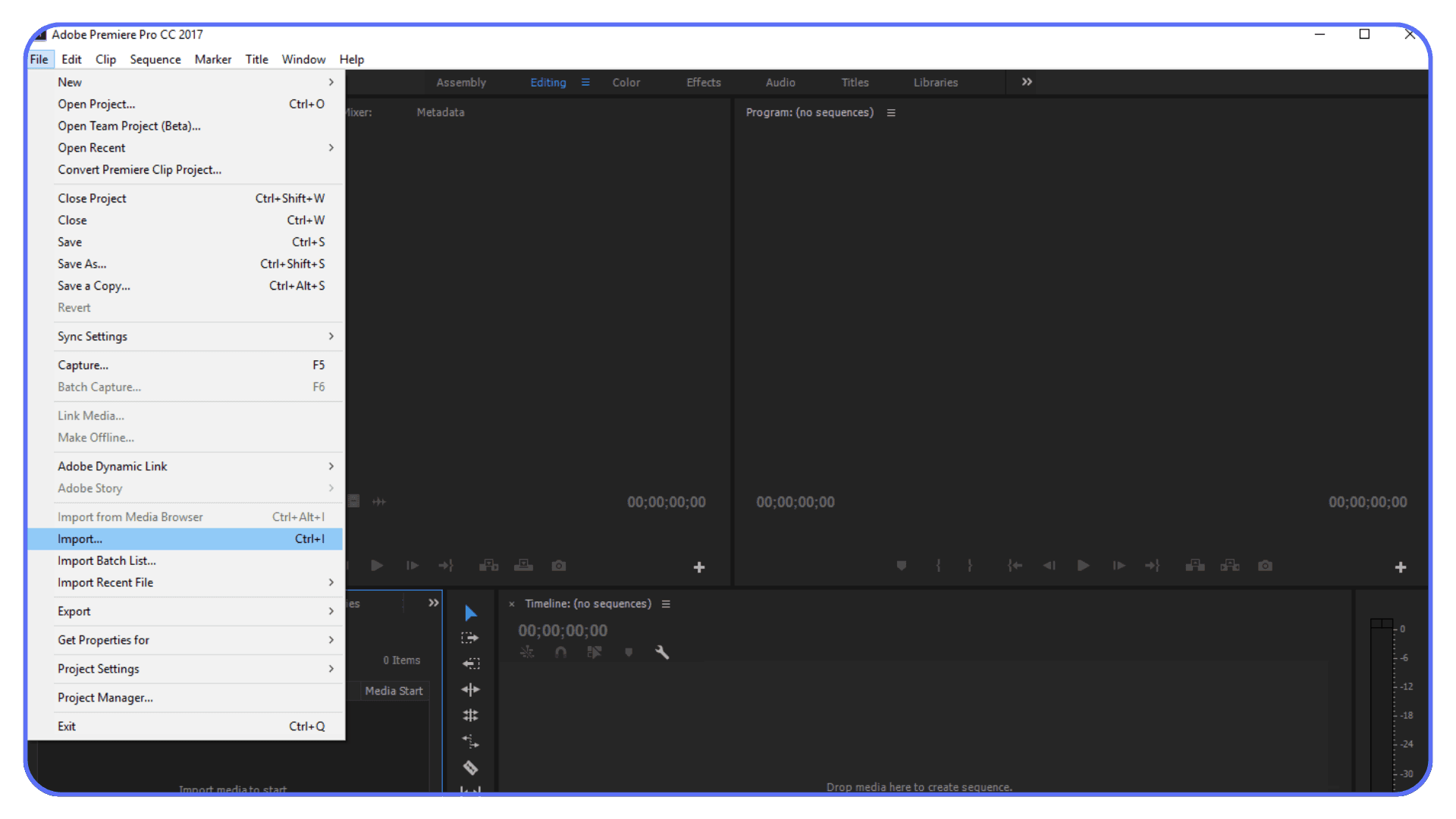

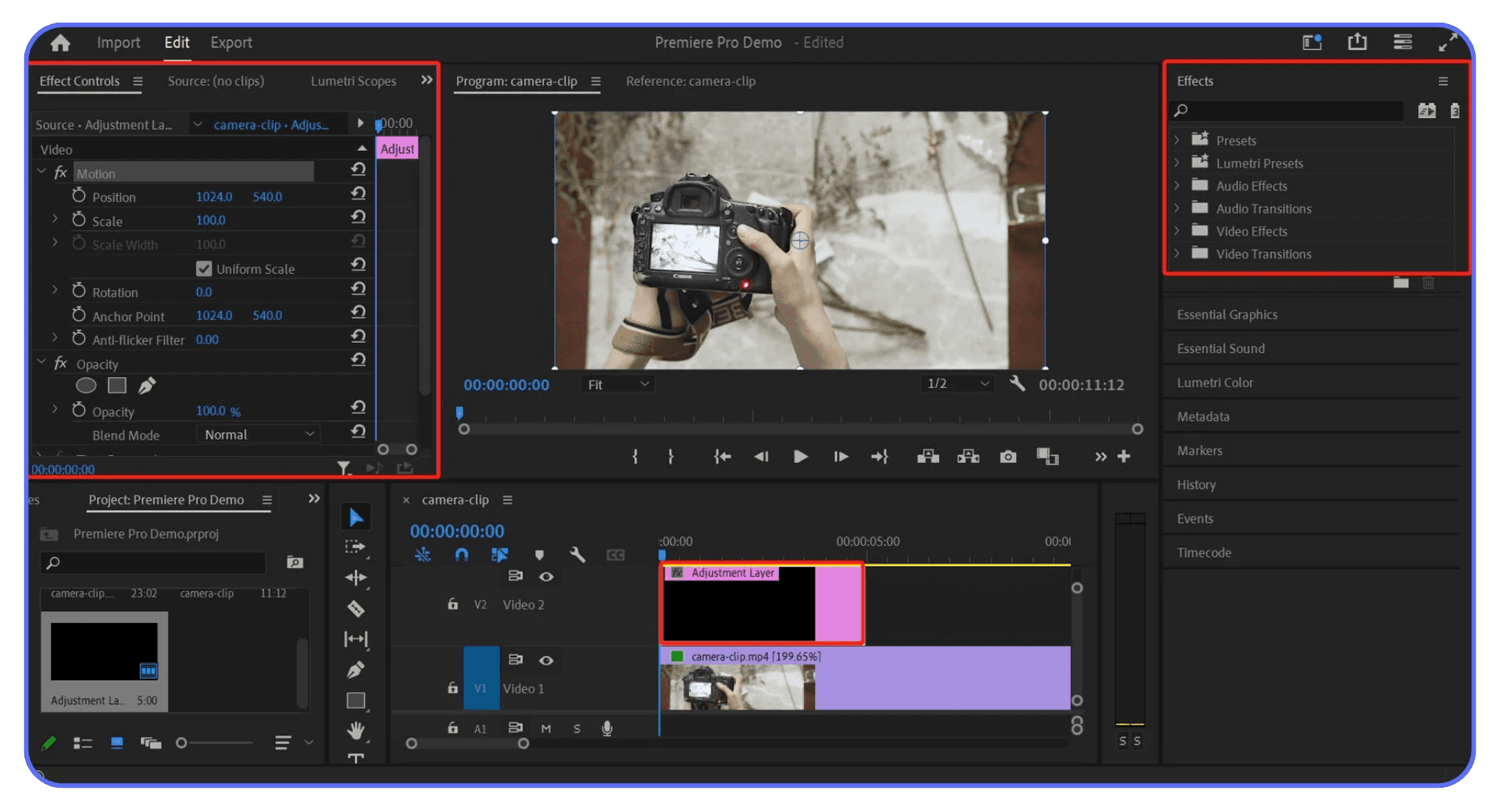

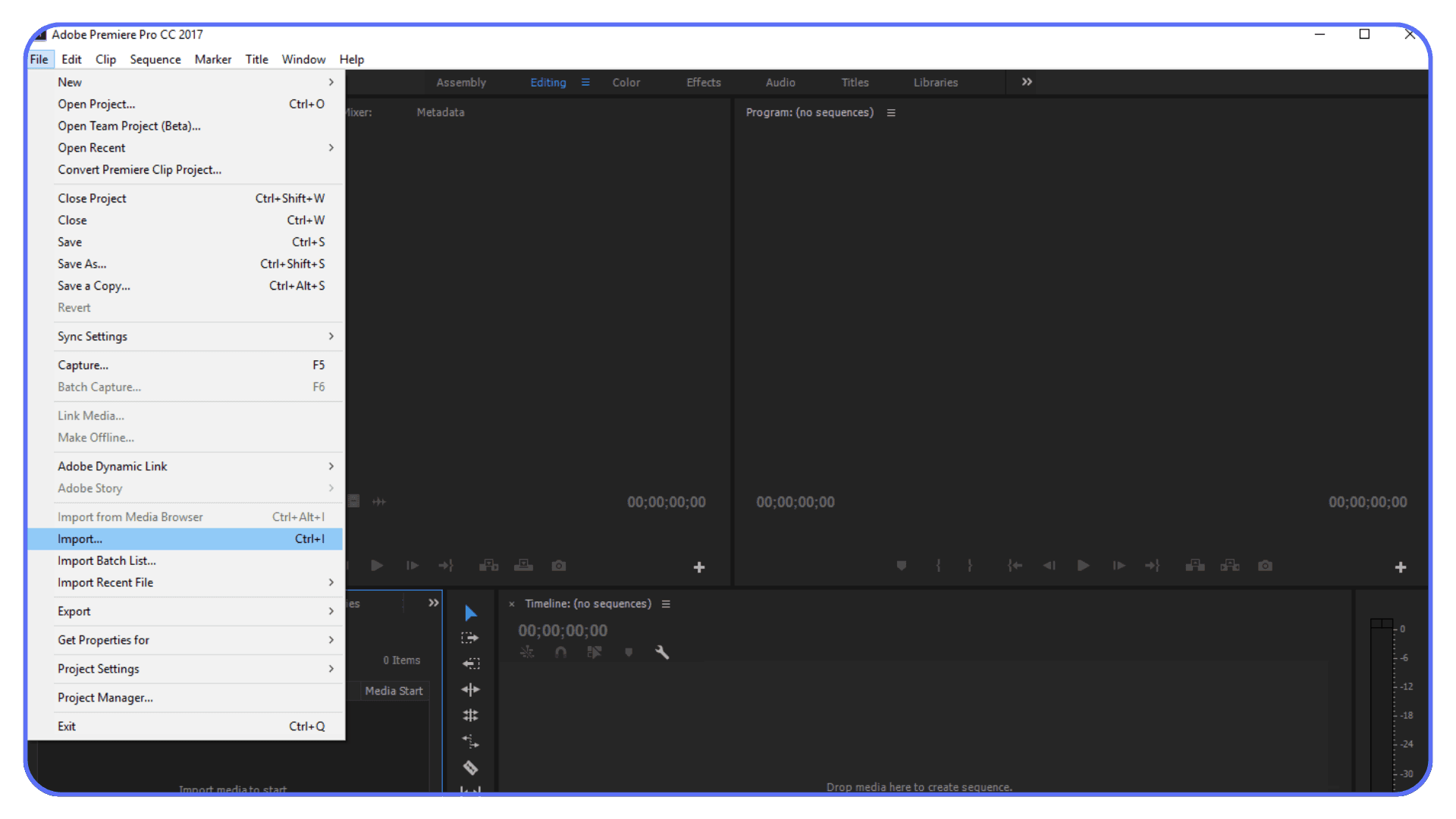

Adobe Premiere Pro

Premiere’s XML export is deceptively simple. You export a Final Cut Pro XML, even though you’re not in Final Cut. That alone should set expectations.

Premiere writes older-style XML, which means modern timeline features don’t always translate cleanly. Adjustment layers, nested sequences, some effects stacks. All risky.

Before exporting, simplify. Nesting inside nesting is a bad idea. Flatten where you can. Trim unused tracks. Remove disabled clips. Premiere will happily include things you forgot were there.

One thing I always recommend: test the XML back into Premiere itself. Import it into a fresh project. If it doesn’t come back clean there, it definitely won’t behave somewhere else.

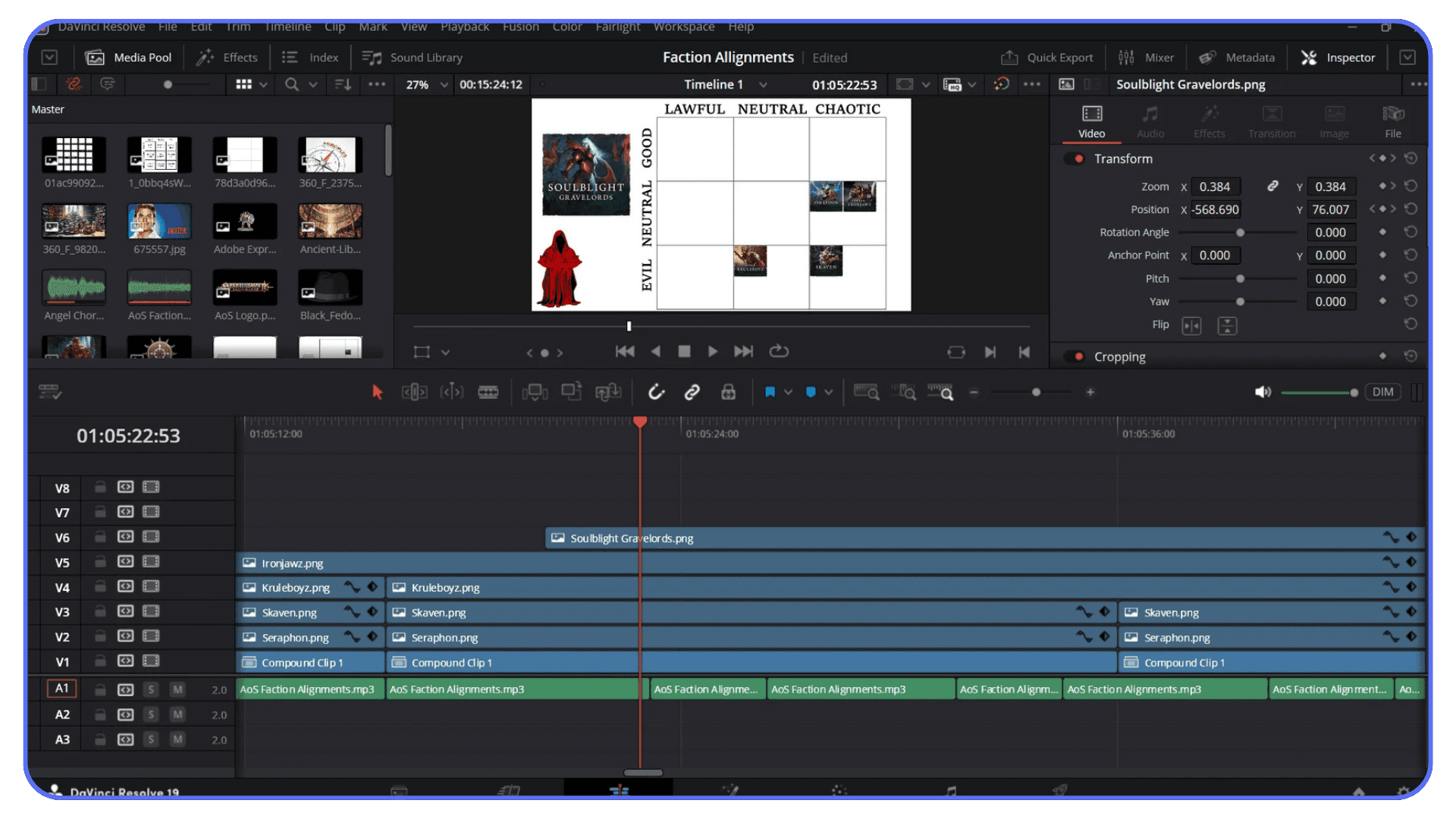

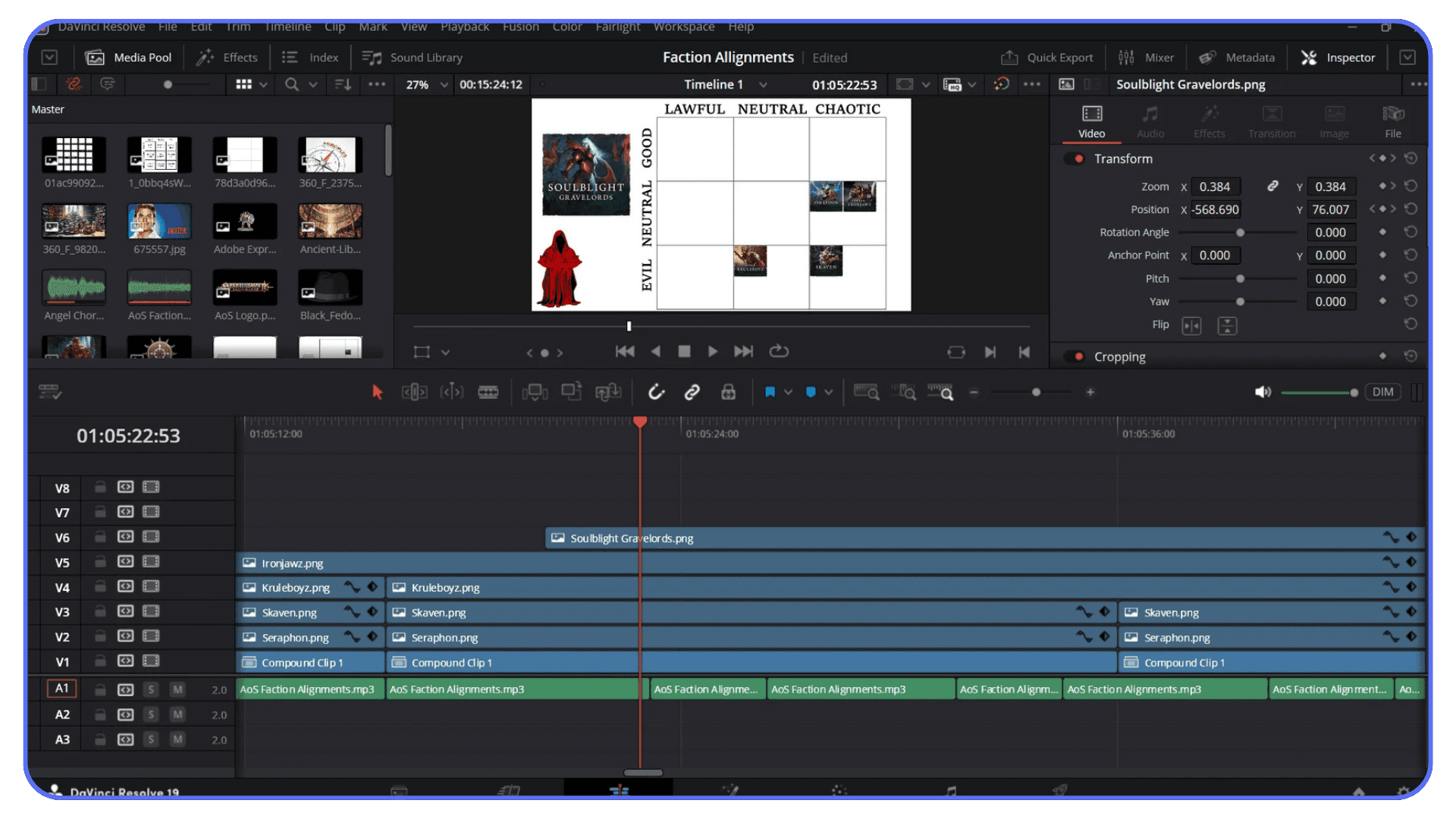

DaVinci Resolve

Resolve is the closest thing we have to a universal translator. It reads and writes multiple XML flavors and generally does a solid job interpreting timelines from other NLEs.

When exporting, pay attention to which XML type you’re creating. Resolve can output Final Cut XML, Premiere-friendly XML, and more. Match the destination, not your source.

Resolve also gives you options for how clips are linked, how handles are treated, and how sizing is interpreted. These checkboxes matter. Don’t just accept defaults.

I’ve seen Resolve save entire projects simply by acting as the middle step. Import the messy XML, clean the timeline, then export a new XML that behaves better on the other end.

The common theme here is restraint. The simpler the timeline at export, the better the XML survives. XML rewards boring, disciplined timelines and punishes clever ones. Keep that in mind before you click export.

Importing XML: What a “Good” Result Actually Looks Like

A successful XML import rarely looks perfect. That’s the first mindset shift.

If you’re expecting the timeline to open exactly the way it left the original NLE, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment. A good import is one where the structure is right and the damage is predictable.

When things go well, here’s what you should see. All the clips are there. The cut points line up. The overall duration matches. Audio and video are in sync. If you scrub through and nothing feels obviously wrong, that’s already a win.

What you should not expect is polish. Titles will usually need to be rebuilt. Transitions might default to something basic or disappear entirely. Effects that rely on proprietary tools almost never survive. Speed changes and retiming often need a close inspection, especially around cuts.

In my experience, a clean XML import still requires a cleanup pass. For a short-form piece, that might be ten or fifteen minutes. For a long-form project, thirty to sixty minutes isn’t unusual. That’s normal. Anyone telling you otherwise either got lucky or hasn’t checked closely enough.

Audio deserves special attention on import. Even when everything is technically present, the logic can be off. Dialogue that used to live neatly on one role or track may now be scattered. Submixes often collapse. Automation can vanish. The sound is there, but the organization isn’t.

One thing that helps is opening the XML in a fresh project, not an existing one. Let the NLE build its interpretation from scratch. Fewer conflicts. Fewer ghosts.

A “good” XML import doesn’t save you from work. It saves you from rebuilding the edit. That distinction matters. If the edit comes across intact and you’re fixing details instead of re-cutting scenes, the XML did its job.

Anything better than that is a bonus.

Resolve handles XML well, but it’s demanding. Picking from the best laptops to smoothly run DaVinci Resolve helps avoid slowdowns during conform and grading.

The Most Common XML Problems and How Editors Actually Fix Them

This is the part nobody likes to talk about because it isn’t glamorous. It’s the cleanup. The quiet half hour where you confirm that, yes, the timeline is usable, and no, it didn’t come across clean.

#1. Frame Rate Issues Come First (Almost Always)

Everything looks fine until you check project settings and realize the timeline is being interpreted differently. A 23.98 project opens as 24. A 25 timeline behaves like 50.

When this happens, stop immediately. Fix the project settings before touching anything else. If you start trimming clips before correcting the timebase, you’ll chase problems forever.

#2. Offline Media That Isn’t Actually Missing

This one’s a classic. Most of the time, the files are there. The paths just don’t match.

This is why consistent folder structure matters more than people think. If the media was consolidated before export, relinking is usually a one-click fix. If it wasn’t, you’re relinking clip by clip and questioning your life choices.

#3. Track Chaos and Lost Organization

This shows up a lot, especially when moving between clip-based and track-based systems. Dialogue ends up on five tracks. Music and effects get mixed together.

XML doesn’t understand why you organized things the way you did. It only knows where clips landed. The fastest fix is usually to regroup manually instead of trying to force the original logic back into place.

#4. Broken Transitions and Missing Effects

Transitions and effects are often faster to rebuild than troubleshoot. If a dissolve doesn’t translate properly, delete it and add a new one. Same duration. Same timing.

Trying to salvage a broken effect almost always takes longer than recreating it cleanly.

#5. Multicam Reality Checks

Multicam edits deserve a reality check. If the XML flattened your multicam clips, accept it and move on unless angle flexibility is absolutely required.

Rebuilding multicam from a broken import is rarely worth the effort.

#6. The Mindset That Makes This Easier

The biggest mistake I see is editors treating these problems as failures. They aren’t. They’re expected friction. XML is doing exactly what it’s capable of doing, no more, no less.

Once you approach cleanup as a normal step instead of a surprise, the whole process becomes calmer. You stop fighting the tool and start working with its limits. That’s when XML goes from frustrating to tolerable.

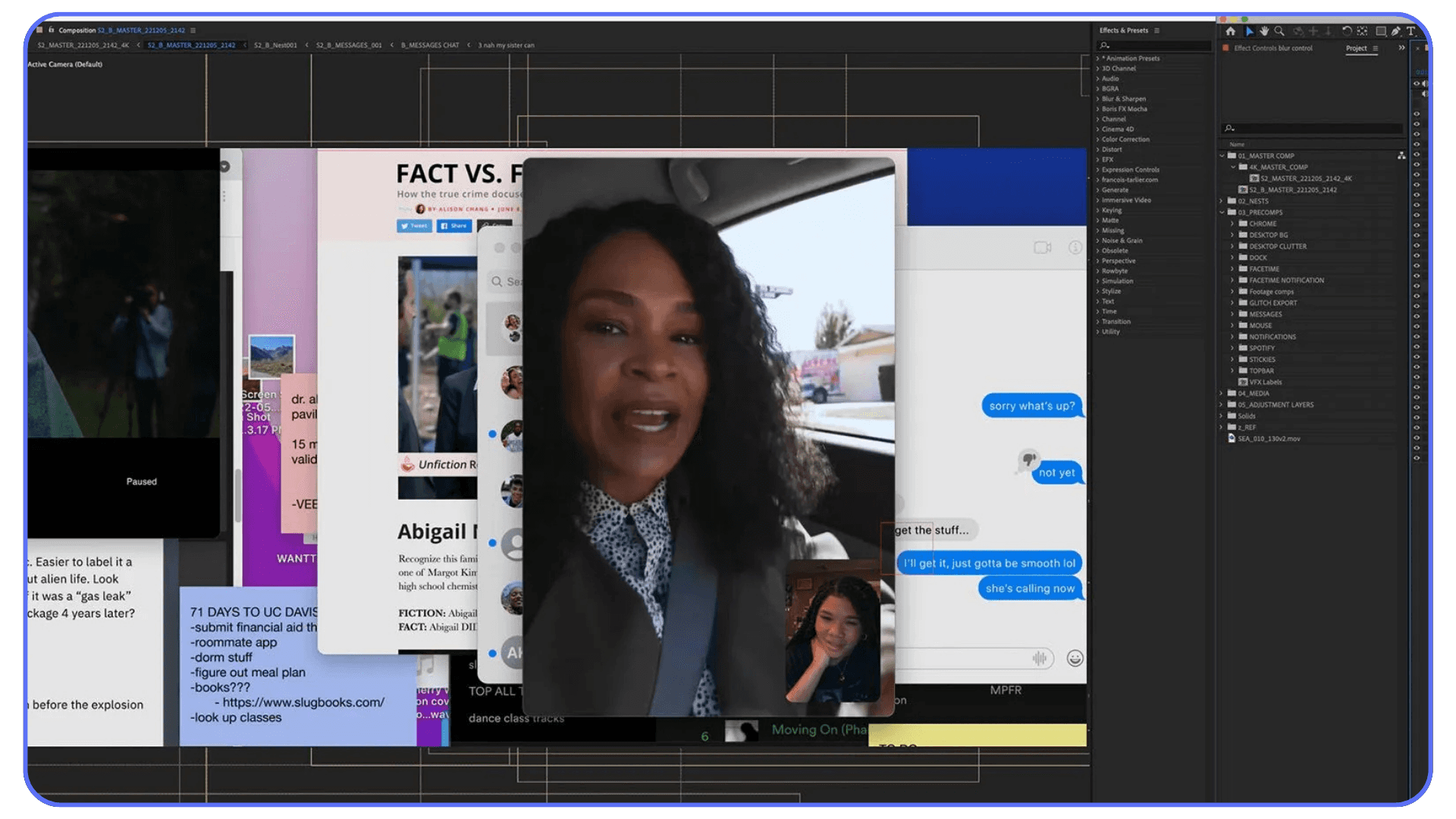

Cleanup after an XML handoff is faster when you know your tools well. These After Effects keyboard shortcuts save real time.

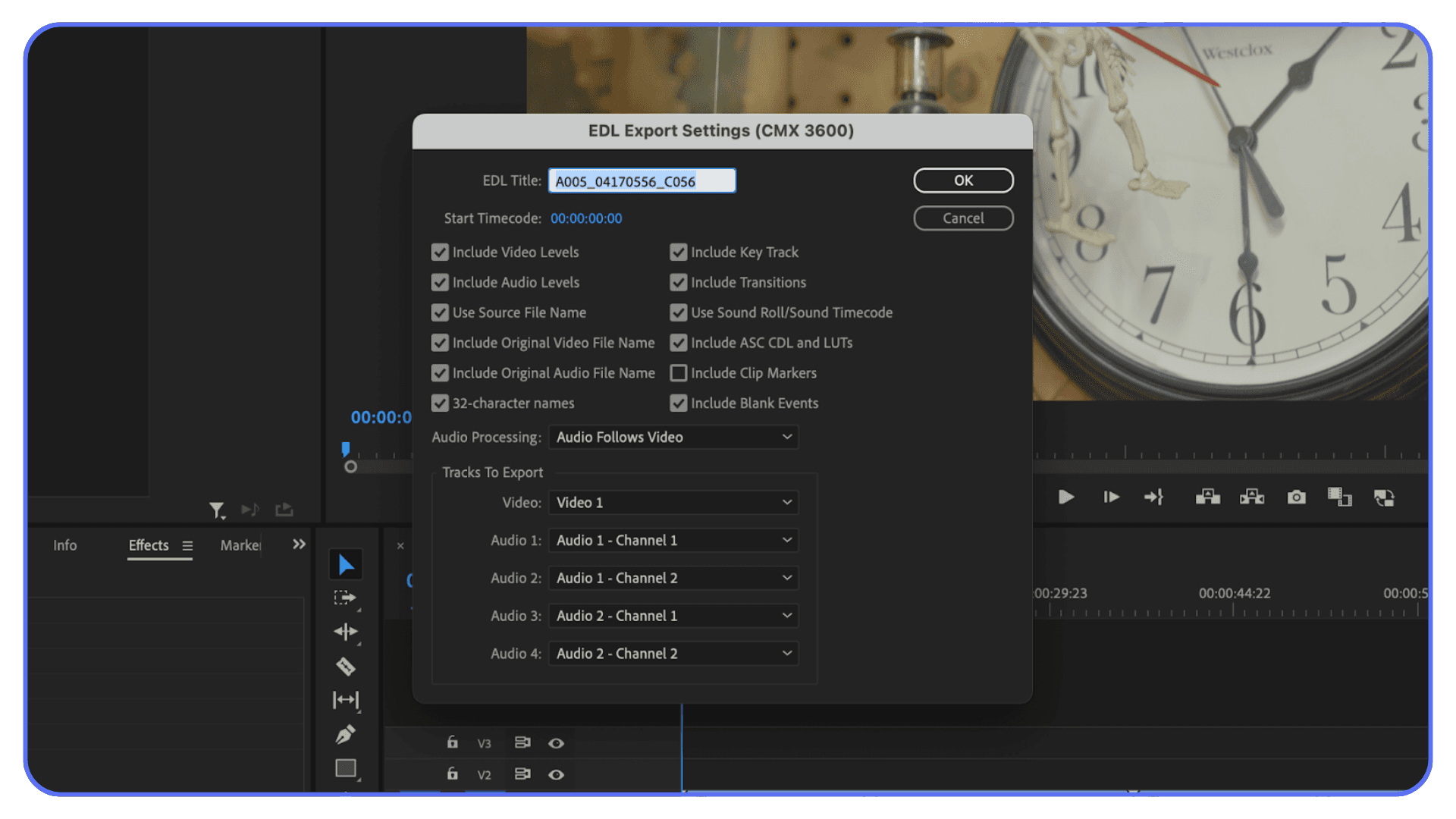

When XML Is the Wrong Tool

This is important, and it doesn’t get said often enough. XML isn’t always the right answer. Sometimes it’s barely an answer at all.

If the project is audio-heavy, like a dialogue-driven film heading to a sound mixer, XML is usually a poor choice. Too much intent gets lost. Roles, buses, automation. All of that matters in sound, and XML has a habit of flattening nuance. That’s where AAF makes more sense. It carries audio information in a way post-audio tools actually respect.

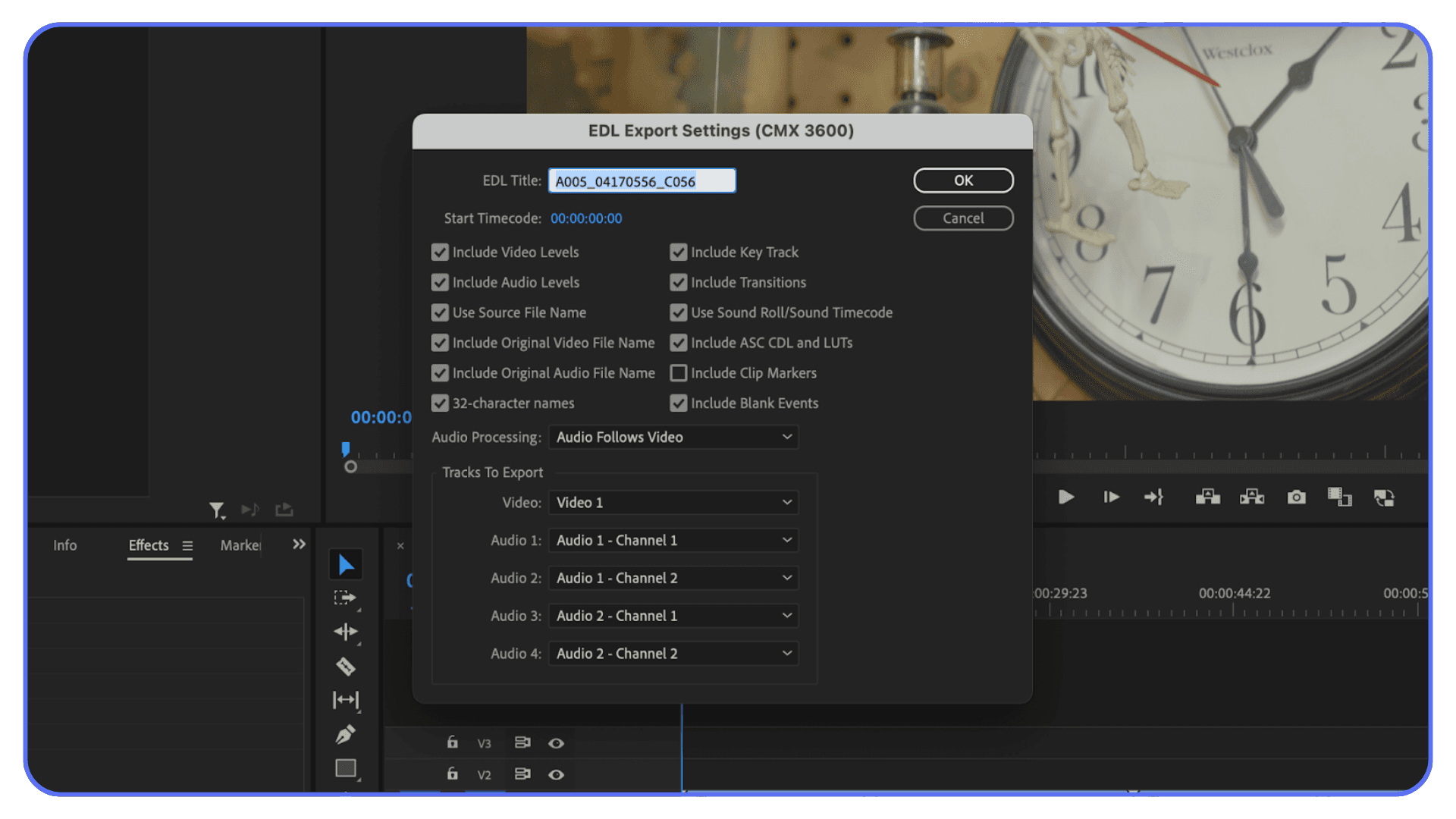

EDL still has a place too, even though it feels ancient. If the job is a simple online conform or a color pass with clean cuts and no fancy layering, an EDL can be more reliable than XML. It’s dumb, but it’s predictable. Sometimes boring is exactly what you want.

There are also moments where the smartest move is skipping timeline translation altogether. Export a reference video with burn-ins. Send handles. Let the next stage rebuild from a known-good visual. It feels like extra work, but it can save days when timelines are fragile or deadlines are unforgiving.

I’ve also learned to avoid XML when the timeline is still in flux. If the edit isn’t locked, every round-trip compounds the mess. XML works best when the structure is stable and changes are intentional, not constant.

The takeaway here isn’t that XML is bad. It’s that it’s specific. It shines in certain handoffs and falls apart in others. Knowing when not to use it is just as valuable as knowing how to export it properly.

Choosing the right handoff format upfront is one of those quiet decisions that separates smooth post workflows from chaotic ones.

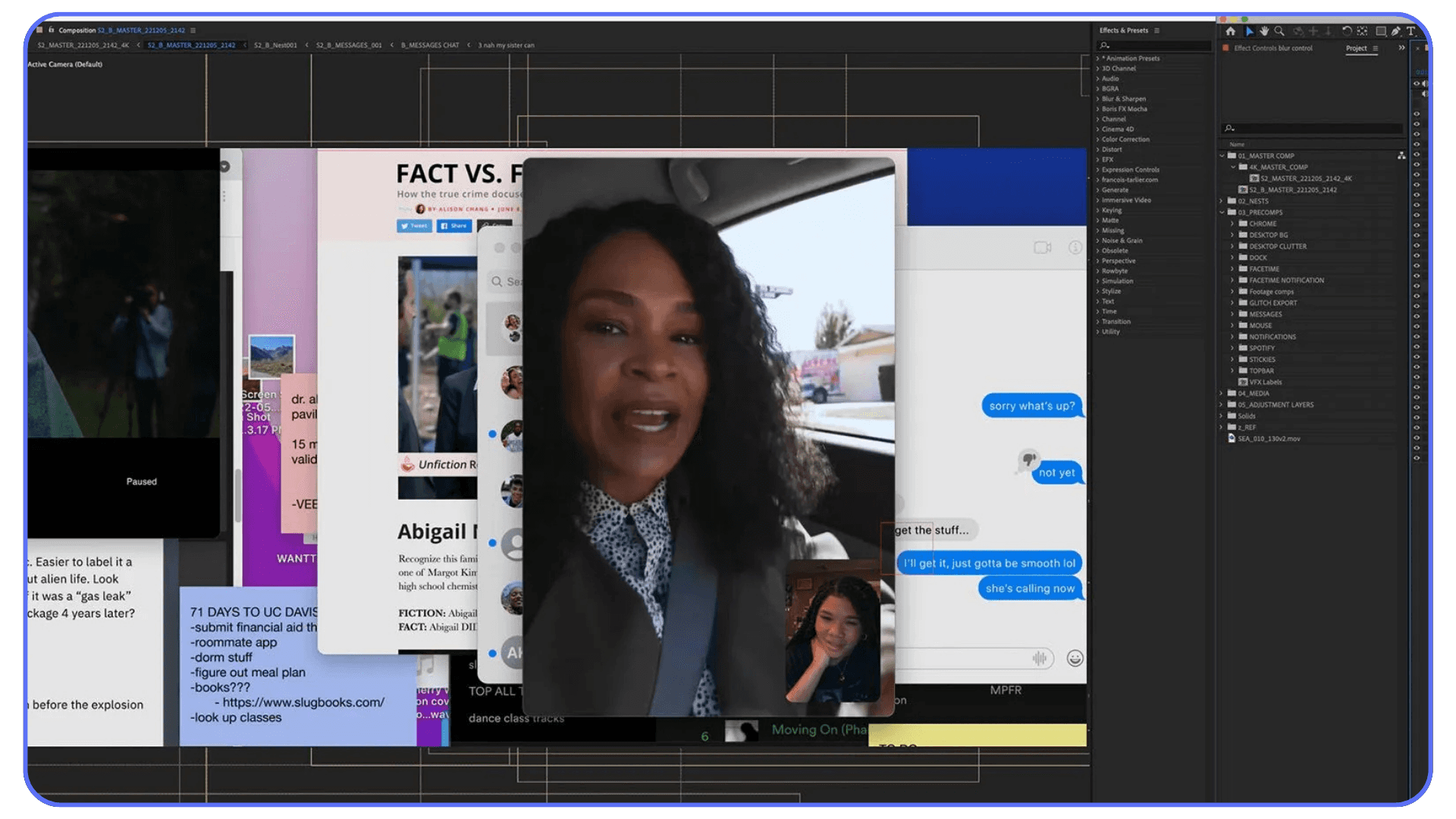

Motion work doesn’t have to stay tied to a desk. There are now workable setups for running Adobe After Effects on iPad through remote systems.

Habits That Make XML Transfers Suck Less

There’s no setting that magically fixes XML. What actually helps are boring habits you build over time. The kind that feel unnecessary until the day they save you.

#1. Lock Down Your Media Before You Export

Media discipline is the biggest one. Before exporting XML, consolidate your media and lock the folder structure. If every clip lives where the XML thinks it lives, relinking becomes trivial.

If not, you’re hunting for files manually. Guess which one happens more often.

#2. Name Things Like Someone Else Will Read Them

Naming matters more than people admit. Clip names, sequence names, even audio tracks.

Clear names make it easier to spot problems after import. They also help the receiving editor understand your intent without a phone call or a screen share.

#3. Test the XML Before It Matters

Test exports are underrated. Don’t wait until the final handoff to see if the XML works.

Export a small section. Import it into the destination NLE yourself if you can. Five minutes of testing can save an hour of cleanup later.

#4. Keep Versions Like Your Sanity Depends on It

Keep versions. Always.

Duplicate the project before exporting XML and label it clearly. If something goes wrong, you want to be able to go back without guessing which file was the “good” one.

#5. Flatten What Doesn’t Need to Travel

Flatten complexity when you can. Nested sequences, compound clips, adjustment layers. All useful inside your own edit. All risky once the timeline leaves.

If the complexity doesn’t need to travel, don’t make it travel.

#6. Discipline Beats Luck Every Time

I’ve noticed that editors who rarely struggle with XML aren’t smarter or luckier. They’re just more disciplined.

They assume the handoff will be messy and prepare for it. That mindset alone fixes more problems than any checkbox ever will.

XML struggles even more once After Effects is involved. Hardware choice becomes critical, which is why this list of laptops and prebuilt PCs for After Effects is useful.

A Real XML Handoff Scenario

Here’s a situation I’ve seen more times than I can count.

A 45-minute documentary cut in Final Cut. Locked picture. Dialogue-heavy. A few speed changes. Light temp color. Nothing exotic. The colorist works in DaVinci Resolve. Timeline needs to move. Deadline’s real.

The editor exports an XML, sends it over, and everyone crosses their fingers.

On import, the structure is mostly there. Cuts line up. Sync holds. That’s the good news. The less good news shows up five minutes later. All titles are gone. Speed ramps came through, but not quite right. Audio roles collapsed into a handful of tracks that technically work, but don’t reflect how the edit was organized.

None of this is surprising.

Instead of trying to fix everything at once, the colorist focuses on what matters for the job. Picture first. They confirm timing against a reference export. They ignore titles completely. Speed changes get checked shot by shot. Anything questionable gets flagged, not “fixed,” until there’s confirmation.

The editor stays available, but not glued to the phone. They already sent a reference video with burn-in timecode and clip names. When a shot feels off, it’s easy to confirm whether it’s an XML issue or an original edit choice.

Total cleanup time before grading starts? About 25 minutes.

That’s the part people miss. The workflow didn’t succeed because the XML was perfect. It succeeded because expectations were realistic. Each person knew what XML was responsible for and what it wasn’t.

If the editor had tried to preserve every title animation or insisted the roles come through untouched, the handoff would’ve dragged on for hours. Instead, they let XML do what it’s good at. Move the edit. Preserve timing. Get out of the way.

That’s what a healthy XML handoff looks like. Not flawless. Just efficient enough to keep the project moving.

A lot of XML headaches come down to mismatched hardware. This PC build and buying guide for Premiere Pro shows which components actually matter.

Why XML Workflows Depend on the Editing Environment

By the time you’ve moved a few timelines around, a pattern becomes obvious. Most XML problems don’t come from the XML itself. They come from everything wrapped around it.

Different operating systems interpret media differently. Different NLE versions read the same XML slightly differently. Plugins that exist on one machine don’t exist on another. Even hardware matters once timelines get heavy. Suddenly the same XML behaves fine in one place and falls apart in another.

This is why two editors can open the same XML and have completely different experiences.

One sees a usable timeline with minor cleanup. The other sees offline media, missing effects, and performance issues that make playback miserable. Same file. Different environment.

XML is sensitive to variables. The more variables you introduce, different OS, different software versions, different plugins, different hardware, the more fragile the handoff becomes. That’s not a moral failing. It’s just how these tools work.

This is also why XML workflows tend to feel smoother inside studios or post houses. Not because they’re smarter, but because their environments are controlled. Same builds. Same setups. Fewer surprises.

Once timelines start moving between freelancers, remote collaborators, or external partners, that control disappears. And that’s usually when XML gets blamed for things it didn’t actually break.

In Premiere, XML issues often show up faster on underpowered systems, especially when the GPU isn’t pulling its weight. This guide on choosing the best GPU for Premiere Pro explains why.

Using Vagon Cloud Computer to Stabilize XML-Based Workflows

This is where Vagon Cloud Computer fits into the picture very cleanly.

Instead of sending an XML out into the wild and hoping it behaves on someone else’s machine, you bring the collaborators into the same environment. Same operating system. Same NLE version. Same plugins. Same media paths. The XML opens where it was meant to be opened.

No one installs anything locally. No one downgrades or updates software just to match a project. If the timeline was cut in a specific setup, that setup is what everyone uses.

This matters a lot once XML becomes part of your handoff process. Color, finishing, revisions, pickups. All the stages where timelines move but shouldn’t change. When everyone is working inside the same cloud workstation, XML stops being a compatibility gamble and becomes a predictable bridge.

There’s also the performance side. Long timelines, high-bitrate codecs, multicam interviews. These are exactly the projects where XML handoffs happen and local machines start to struggle. Running the project on cloud hardware keeps playback responsive and exports reasonable, even when the timeline is dense.

The real value here isn’t speed or flexibility on paper. It’s consistency. XML works best when the environment doesn’t reinterpret it. Vagon gives you a shared, neutral space where the timeline behaves the same way for everyone involved.

If XML is how your projects move between people and tools, controlling the environment is one of the smartest ways to reduce friction. This is one of the cleaner ways I’ve seen teams actually do that.

Some editors now review or tweak timelines remotely, including setups that let you use Adobe Premiere Pro on iPad without relying on local hardware.

Final Thoughts

XML isn’t broken. It’s just picky.

It does one job reasonably well and everything else reluctantly. When you ask it to move structure between NLEs, it usually shows up. When you ask it to preserve nuance, style, or intent, it quietly opts out. That’s not a bug. That’s the deal.

The editors who have the least trouble with XML aren’t the ones with the fanciest setups or the deepest technical knowledge. They’re the ones who limit variables. They simplify timelines before export. They choose the right handoff format. They expect cleanup. And they pay attention to the environment where that XML is going to land.

Once you stop treating XML like a magic trick and start treating it like a controlled transfer, the whole process gets calmer. Fewer surprises. Fewer late-night fixes. Less blaming the file for problems it never promised to solve.

And if there’s one thing I’ve learned after years of moving timelines around, it’s this: XML works best when everything around it is boring and consistent. Same tools. Same versions. Same expectations.

Get that part right, and XML stops feeling like a gamble. It just becomes another tool in the workflow. Not perfect. But reliable enough to keep projects moving when they need to.

FAQs

1. Does XML move my media files too?

No. XML only carries instructions. It tells the destination NLE where clips should be and how they’re cut, but it doesn’t include the actual media. If the files aren’t accessible or the paths don’t match, you’ll be relinking. Every time.

2. Which NLE handles XML the best?

In my experience, DaVinci Resolve is the most forgiving. It reads and writes multiple XML flavors and tends to interpret timelines more sensibly. That’s why so many editors quietly use it as a middle step, even if they don’t do the final work there.

3. Why do my effects disappear after importing XML?

Because most effects aren’t universal. A blur, title, or transition in Final Cut Pro doesn’t mean anything to Adobe Premiere Pro, and vice versa. XML will usually drop or simplify anything it can’t translate. This is normal.

4. Are speed ramps safe to transfer with XML?

Sometimes. Simple speed changes often survive. Complex ramps with keyframes are risky. Always check them manually after import. If timing is critical, compare against a reference export.

5. Why did my frame rate change even though both timelines match?

This usually comes down to interpretation, not settings. Timebase, field order, or fractional frame rates can cause the destination NLE to read the XML differently. Always verify project settings immediately after import, before touching the timeline.

6. Is XML better than AAF or EDL?

It depends on the job. XML is better for preserving edit structure across modern NLEs. AAF is usually better for audio-heavy handoffs. EDL is old, limited, and surprisingly reliable for simple conforms. There’s no single “best” format, only the least painful one for the task.

7. Should I flatten multicam before exporting XML?

If the receiving editor doesn’t need to switch angles, yes. Flattening trades flexibility for stability, and stability usually wins during handoffs.

8. How long should cleanup take after a good XML import?

For short projects, ten to twenty minutes is normal. For long-form timelines, thirty to sixty minutes isn’t unusual. If you’re rebuilding scenes, something went wrong earlier in the process.

9. What’s the biggest mistake people make with XML?

Expecting perfection. XML is a starting point, not a finish line. The editors who struggle the most are usually the ones expecting it to behave like a full project file.

It usually starts with a simple request.

“Can you send the timeline?”

Not a video. Not stems. The actual timeline. And you look at the deadline, glance at your project, and tell yourself the lie we all tell ourselves. This should be easy.

It never is.

The moment XML enters the picture, you stop editing and start translating. Different apps. Different rules. Same timeline, somehow behaving differently the second it leaves home. You export the XML, send it off, and wait for the inevitable follow-up messages.

Cuts a frame off. Clips offline. Audio tracks scrambled. Titles gone.

The edit was fine five minutes ago. Now it’s… not.

XML isn’t a magic handoff. It’s a fragile truce between NLEs. Sometimes it holds. Sometimes it breaks immediately. And if you’ve done this more than once, you already know which side of that coin it usually lands on.

That’s the reality we’re dealing with here.

What XML Actually Is (and What It Isn’t)

Here’s the part people usually misunderstand, even experienced editors.

An XML file doesn’t move your project. It describes it.

Think of XML as a set of instructions. Where clips start and stop. Which files are used. How tracks are stacked. Basic timing, basic structure, basic relationships. That’s it. No media. No renders. No real understanding of creative intent.

This is why XML can feel both powerful and deeply disappointing at the same time.

In my experience, XML is great at one thing: rebuilding the skeleton of a timeline somewhere else. It knows your cuts. It knows your clip order. It usually knows your timecode. If that’s all you need, you’re in decent shape.

The problems start when you expect more than that.

Effects don’t translate cleanly because they aren’t universal. A blur in one NLE isn’t the same blur in another. Titles are often proprietary. Motion settings, keyframes, speed ramps, adjustment layers… all fair game to get ignored or misinterpreted. XML isn’t being lazy. It just doesn’t know what to do with those instructions.

Audio is another trap. Track-based editors and clip-based editors think very differently. XML tries to bridge that gap, but it doesn’t always succeed. You’ll see clips move tracks, automation disappear, or roles collapse into something that technically works but feels wrong.

And no, XML isn’t broken because of this. It’s just limited.

I’ve noticed a lot of frustration comes from treating XML like a project file replacement. It isn’t. It’s closer to a translator that only speaks half the language. Enough to get the point across. Not enough to preserve nuance.

That’s also why XML still matters. As flawed as it is, it’s the closest thing we have to a shared vocabulary between NLEs. When timelines need to move between people, apps, or stages of post, XML is usually the least bad option on the table.

The key is knowing what you’re asking it to carry. Structure, yes. Polish, no. Once you internalize that, the whole workflow gets a lot less frustrating.

Why XML Transfers Break More Often Than People Admit

Most XML failures aren’t dramatic. They’re subtle. And that’s what makes them dangerous.

The timeline opens. Nothing crashes. At first glance, it looks fine. Then you zoom in. A cut is one frame late. An audio clip starts a few milliseconds early. A transition is technically there, but not doing what it was doing before. Individually, these are small problems. Stack enough of them together and your “quick handoff” turns into an hour of cleanup.

One big reason this happens is that NLEs don’t agree on how timelines should behave. They all cut video, sure, but under the hood they’re wildly opinionated. Track-based vs clip-based. Different assumptions about timecode, sample rates, even what “a frame” means in edge cases.

Effects are the most obvious casualty. If the destination app doesn’t have an equivalent effect, XML just shrugs and moves on. Sometimes you get placeholders. Sometimes you get nothing. Speed changes and retiming are especially fragile. Anything involving keyframes should be treated as guilty until proven innocent.

Multicam is another common failure point. Many XML exports flatten multicam clips into a single angle. The edit stays intact, but the flexibility is gone. That’s fine for finishing. It’s a nightmare if you expected to keep adjusting angles.

Then there’s frame rate drift. This one catches people off guard. The timeline frame rate might technically match, but field order, timebase interpretation, or fractional rates can cause the destination NLE to read the project differently. Suddenly a 25fps timeline behaves like 50. Or audio slowly slips over time. No error message. Just vibes. Bad ones.

Audio routing deserves its own warning label. Roles, submixes, and buses rarely survive intact. XML can move clips, but it struggles to preserve intent. You’ll often end up with audio that’s technically there but logically scrambled.

I think the biggest myth is that XML problems mean someone did something wrong. Most of the time, nobody did. You just crossed a boundary where assumptions stopped lining up.

That’s why experienced editors don’t expect a perfect transfer. They expect a usable starting point. The mistake is believing XML will give you more than that.

Exporting XML From Different NLEs Without Sabotaging Yourself

Most XML disasters don’t happen on import. They happen right here. At export. Quietly.

A lot of editors treat XML export like a final step. Click the menu item, pick a version, send the file. Done. That’s how you end up fixing things later that you could’ve avoided in two minutes up front.

Different NLEs write XML differently, and the choices you make before exporting matter more than the XML version number itself.

Final Cut Pro

Final Cut’s XML is powerful, but it’s also very literal. It exports exactly what’s in the timeline, including complexity you may have forgotten about.

Compound clips are the first trap. XML will carry them, but not every app knows what to do with them. If the timeline is leaving Final Cut, flatten compounds unless you have a very good reason not to. Same goes for multicam. If the receiving editor doesn’t need angle control, flatten it. You’re trading flexibility for predictability, and predictability wins most of the time.

Roles are another gotcha. They’re great inside Final Cut. Outside of it, they often collapse into basic tracks. Before exporting, clean them up. Fewer roles. Clear intent.

And always export the newest XML version supported by the destination app. Newer versions usually behave better, but only if the other side can read them properly.

Adobe Premiere Pro

Premiere’s XML export is deceptively simple. You export a Final Cut Pro XML, even though you’re not in Final Cut. That alone should set expectations.

Premiere writes older-style XML, which means modern timeline features don’t always translate cleanly. Adjustment layers, nested sequences, some effects stacks. All risky.

Before exporting, simplify. Nesting inside nesting is a bad idea. Flatten where you can. Trim unused tracks. Remove disabled clips. Premiere will happily include things you forgot were there.

One thing I always recommend: test the XML back into Premiere itself. Import it into a fresh project. If it doesn’t come back clean there, it definitely won’t behave somewhere else.

DaVinci Resolve

Resolve is the closest thing we have to a universal translator. It reads and writes multiple XML flavors and generally does a solid job interpreting timelines from other NLEs.

When exporting, pay attention to which XML type you’re creating. Resolve can output Final Cut XML, Premiere-friendly XML, and more. Match the destination, not your source.

Resolve also gives you options for how clips are linked, how handles are treated, and how sizing is interpreted. These checkboxes matter. Don’t just accept defaults.

I’ve seen Resolve save entire projects simply by acting as the middle step. Import the messy XML, clean the timeline, then export a new XML that behaves better on the other end.

The common theme here is restraint. The simpler the timeline at export, the better the XML survives. XML rewards boring, disciplined timelines and punishes clever ones. Keep that in mind before you click export.

Importing XML: What a “Good” Result Actually Looks Like

A successful XML import rarely looks perfect. That’s the first mindset shift.

If you’re expecting the timeline to open exactly the way it left the original NLE, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment. A good import is one where the structure is right and the damage is predictable.

When things go well, here’s what you should see. All the clips are there. The cut points line up. The overall duration matches. Audio and video are in sync. If you scrub through and nothing feels obviously wrong, that’s already a win.

What you should not expect is polish. Titles will usually need to be rebuilt. Transitions might default to something basic or disappear entirely. Effects that rely on proprietary tools almost never survive. Speed changes and retiming often need a close inspection, especially around cuts.

In my experience, a clean XML import still requires a cleanup pass. For a short-form piece, that might be ten or fifteen minutes. For a long-form project, thirty to sixty minutes isn’t unusual. That’s normal. Anyone telling you otherwise either got lucky or hasn’t checked closely enough.

Audio deserves special attention on import. Even when everything is technically present, the logic can be off. Dialogue that used to live neatly on one role or track may now be scattered. Submixes often collapse. Automation can vanish. The sound is there, but the organization isn’t.

One thing that helps is opening the XML in a fresh project, not an existing one. Let the NLE build its interpretation from scratch. Fewer conflicts. Fewer ghosts.

A “good” XML import doesn’t save you from work. It saves you from rebuilding the edit. That distinction matters. If the edit comes across intact and you’re fixing details instead of re-cutting scenes, the XML did its job.

Anything better than that is a bonus.

Resolve handles XML well, but it’s demanding. Picking from the best laptops to smoothly run DaVinci Resolve helps avoid slowdowns during conform and grading.

The Most Common XML Problems and How Editors Actually Fix Them

This is the part nobody likes to talk about because it isn’t glamorous. It’s the cleanup. The quiet half hour where you confirm that, yes, the timeline is usable, and no, it didn’t come across clean.

#1. Frame Rate Issues Come First (Almost Always)

Everything looks fine until you check project settings and realize the timeline is being interpreted differently. A 23.98 project opens as 24. A 25 timeline behaves like 50.

When this happens, stop immediately. Fix the project settings before touching anything else. If you start trimming clips before correcting the timebase, you’ll chase problems forever.

#2. Offline Media That Isn’t Actually Missing

This one’s a classic. Most of the time, the files are there. The paths just don’t match.

This is why consistent folder structure matters more than people think. If the media was consolidated before export, relinking is usually a one-click fix. If it wasn’t, you’re relinking clip by clip and questioning your life choices.

#3. Track Chaos and Lost Organization

This shows up a lot, especially when moving between clip-based and track-based systems. Dialogue ends up on five tracks. Music and effects get mixed together.

XML doesn’t understand why you organized things the way you did. It only knows where clips landed. The fastest fix is usually to regroup manually instead of trying to force the original logic back into place.

#4. Broken Transitions and Missing Effects

Transitions and effects are often faster to rebuild than troubleshoot. If a dissolve doesn’t translate properly, delete it and add a new one. Same duration. Same timing.

Trying to salvage a broken effect almost always takes longer than recreating it cleanly.

#5. Multicam Reality Checks

Multicam edits deserve a reality check. If the XML flattened your multicam clips, accept it and move on unless angle flexibility is absolutely required.

Rebuilding multicam from a broken import is rarely worth the effort.

#6. The Mindset That Makes This Easier

The biggest mistake I see is editors treating these problems as failures. They aren’t. They’re expected friction. XML is doing exactly what it’s capable of doing, no more, no less.

Once you approach cleanup as a normal step instead of a surprise, the whole process becomes calmer. You stop fighting the tool and start working with its limits. That’s when XML goes from frustrating to tolerable.

Cleanup after an XML handoff is faster when you know your tools well. These After Effects keyboard shortcuts save real time.

When XML Is the Wrong Tool

This is important, and it doesn’t get said often enough. XML isn’t always the right answer. Sometimes it’s barely an answer at all.

If the project is audio-heavy, like a dialogue-driven film heading to a sound mixer, XML is usually a poor choice. Too much intent gets lost. Roles, buses, automation. All of that matters in sound, and XML has a habit of flattening nuance. That’s where AAF makes more sense. It carries audio information in a way post-audio tools actually respect.

EDL still has a place too, even though it feels ancient. If the job is a simple online conform or a color pass with clean cuts and no fancy layering, an EDL can be more reliable than XML. It’s dumb, but it’s predictable. Sometimes boring is exactly what you want.

There are also moments where the smartest move is skipping timeline translation altogether. Export a reference video with burn-ins. Send handles. Let the next stage rebuild from a known-good visual. It feels like extra work, but it can save days when timelines are fragile or deadlines are unforgiving.

I’ve also learned to avoid XML when the timeline is still in flux. If the edit isn’t locked, every round-trip compounds the mess. XML works best when the structure is stable and changes are intentional, not constant.

The takeaway here isn’t that XML is bad. It’s that it’s specific. It shines in certain handoffs and falls apart in others. Knowing when not to use it is just as valuable as knowing how to export it properly.

Choosing the right handoff format upfront is one of those quiet decisions that separates smooth post workflows from chaotic ones.

Motion work doesn’t have to stay tied to a desk. There are now workable setups for running Adobe After Effects on iPad through remote systems.

Habits That Make XML Transfers Suck Less

There’s no setting that magically fixes XML. What actually helps are boring habits you build over time. The kind that feel unnecessary until the day they save you.

#1. Lock Down Your Media Before You Export

Media discipline is the biggest one. Before exporting XML, consolidate your media and lock the folder structure. If every clip lives where the XML thinks it lives, relinking becomes trivial.

If not, you’re hunting for files manually. Guess which one happens more often.

#2. Name Things Like Someone Else Will Read Them

Naming matters more than people admit. Clip names, sequence names, even audio tracks.

Clear names make it easier to spot problems after import. They also help the receiving editor understand your intent without a phone call or a screen share.

#3. Test the XML Before It Matters

Test exports are underrated. Don’t wait until the final handoff to see if the XML works.

Export a small section. Import it into the destination NLE yourself if you can. Five minutes of testing can save an hour of cleanup later.

#4. Keep Versions Like Your Sanity Depends on It

Keep versions. Always.

Duplicate the project before exporting XML and label it clearly. If something goes wrong, you want to be able to go back without guessing which file was the “good” one.

#5. Flatten What Doesn’t Need to Travel

Flatten complexity when you can. Nested sequences, compound clips, adjustment layers. All useful inside your own edit. All risky once the timeline leaves.

If the complexity doesn’t need to travel, don’t make it travel.

#6. Discipline Beats Luck Every Time

I’ve noticed that editors who rarely struggle with XML aren’t smarter or luckier. They’re just more disciplined.

They assume the handoff will be messy and prepare for it. That mindset alone fixes more problems than any checkbox ever will.

XML struggles even more once After Effects is involved. Hardware choice becomes critical, which is why this list of laptops and prebuilt PCs for After Effects is useful.

A Real XML Handoff Scenario

Here’s a situation I’ve seen more times than I can count.

A 45-minute documentary cut in Final Cut. Locked picture. Dialogue-heavy. A few speed changes. Light temp color. Nothing exotic. The colorist works in DaVinci Resolve. Timeline needs to move. Deadline’s real.

The editor exports an XML, sends it over, and everyone crosses their fingers.

On import, the structure is mostly there. Cuts line up. Sync holds. That’s the good news. The less good news shows up five minutes later. All titles are gone. Speed ramps came through, but not quite right. Audio roles collapsed into a handful of tracks that technically work, but don’t reflect how the edit was organized.

None of this is surprising.

Instead of trying to fix everything at once, the colorist focuses on what matters for the job. Picture first. They confirm timing against a reference export. They ignore titles completely. Speed changes get checked shot by shot. Anything questionable gets flagged, not “fixed,” until there’s confirmation.

The editor stays available, but not glued to the phone. They already sent a reference video with burn-in timecode and clip names. When a shot feels off, it’s easy to confirm whether it’s an XML issue or an original edit choice.

Total cleanup time before grading starts? About 25 minutes.

That’s the part people miss. The workflow didn’t succeed because the XML was perfect. It succeeded because expectations were realistic. Each person knew what XML was responsible for and what it wasn’t.

If the editor had tried to preserve every title animation or insisted the roles come through untouched, the handoff would’ve dragged on for hours. Instead, they let XML do what it’s good at. Move the edit. Preserve timing. Get out of the way.

That’s what a healthy XML handoff looks like. Not flawless. Just efficient enough to keep the project moving.

A lot of XML headaches come down to mismatched hardware. This PC build and buying guide for Premiere Pro shows which components actually matter.

Why XML Workflows Depend on the Editing Environment

By the time you’ve moved a few timelines around, a pattern becomes obvious. Most XML problems don’t come from the XML itself. They come from everything wrapped around it.

Different operating systems interpret media differently. Different NLE versions read the same XML slightly differently. Plugins that exist on one machine don’t exist on another. Even hardware matters once timelines get heavy. Suddenly the same XML behaves fine in one place and falls apart in another.

This is why two editors can open the same XML and have completely different experiences.

One sees a usable timeline with minor cleanup. The other sees offline media, missing effects, and performance issues that make playback miserable. Same file. Different environment.

XML is sensitive to variables. The more variables you introduce, different OS, different software versions, different plugins, different hardware, the more fragile the handoff becomes. That’s not a moral failing. It’s just how these tools work.

This is also why XML workflows tend to feel smoother inside studios or post houses. Not because they’re smarter, but because their environments are controlled. Same builds. Same setups. Fewer surprises.

Once timelines start moving between freelancers, remote collaborators, or external partners, that control disappears. And that’s usually when XML gets blamed for things it didn’t actually break.

In Premiere, XML issues often show up faster on underpowered systems, especially when the GPU isn’t pulling its weight. This guide on choosing the best GPU for Premiere Pro explains why.

Using Vagon Cloud Computer to Stabilize XML-Based Workflows

This is where Vagon Cloud Computer fits into the picture very cleanly.

Instead of sending an XML out into the wild and hoping it behaves on someone else’s machine, you bring the collaborators into the same environment. Same operating system. Same NLE version. Same plugins. Same media paths. The XML opens where it was meant to be opened.

No one installs anything locally. No one downgrades or updates software just to match a project. If the timeline was cut in a specific setup, that setup is what everyone uses.

This matters a lot once XML becomes part of your handoff process. Color, finishing, revisions, pickups. All the stages where timelines move but shouldn’t change. When everyone is working inside the same cloud workstation, XML stops being a compatibility gamble and becomes a predictable bridge.

There’s also the performance side. Long timelines, high-bitrate codecs, multicam interviews. These are exactly the projects where XML handoffs happen and local machines start to struggle. Running the project on cloud hardware keeps playback responsive and exports reasonable, even when the timeline is dense.

The real value here isn’t speed or flexibility on paper. It’s consistency. XML works best when the environment doesn’t reinterpret it. Vagon gives you a shared, neutral space where the timeline behaves the same way for everyone involved.

If XML is how your projects move between people and tools, controlling the environment is one of the smartest ways to reduce friction. This is one of the cleaner ways I’ve seen teams actually do that.

Some editors now review or tweak timelines remotely, including setups that let you use Adobe Premiere Pro on iPad without relying on local hardware.

Final Thoughts

XML isn’t broken. It’s just picky.

It does one job reasonably well and everything else reluctantly. When you ask it to move structure between NLEs, it usually shows up. When you ask it to preserve nuance, style, or intent, it quietly opts out. That’s not a bug. That’s the deal.

The editors who have the least trouble with XML aren’t the ones with the fanciest setups or the deepest technical knowledge. They’re the ones who limit variables. They simplify timelines before export. They choose the right handoff format. They expect cleanup. And they pay attention to the environment where that XML is going to land.

Once you stop treating XML like a magic trick and start treating it like a controlled transfer, the whole process gets calmer. Fewer surprises. Fewer late-night fixes. Less blaming the file for problems it never promised to solve.

And if there’s one thing I’ve learned after years of moving timelines around, it’s this: XML works best when everything around it is boring and consistent. Same tools. Same versions. Same expectations.

Get that part right, and XML stops feeling like a gamble. It just becomes another tool in the workflow. Not perfect. But reliable enough to keep projects moving when they need to.

FAQs

1. Does XML move my media files too?

No. XML only carries instructions. It tells the destination NLE where clips should be and how they’re cut, but it doesn’t include the actual media. If the files aren’t accessible or the paths don’t match, you’ll be relinking. Every time.

2. Which NLE handles XML the best?

In my experience, DaVinci Resolve is the most forgiving. It reads and writes multiple XML flavors and tends to interpret timelines more sensibly. That’s why so many editors quietly use it as a middle step, even if they don’t do the final work there.

3. Why do my effects disappear after importing XML?

Because most effects aren’t universal. A blur, title, or transition in Final Cut Pro doesn’t mean anything to Adobe Premiere Pro, and vice versa. XML will usually drop or simplify anything it can’t translate. This is normal.

4. Are speed ramps safe to transfer with XML?

Sometimes. Simple speed changes often survive. Complex ramps with keyframes are risky. Always check them manually after import. If timing is critical, compare against a reference export.

5. Why did my frame rate change even though both timelines match?

This usually comes down to interpretation, not settings. Timebase, field order, or fractional frame rates can cause the destination NLE to read the XML differently. Always verify project settings immediately after import, before touching the timeline.

6. Is XML better than AAF or EDL?

It depends on the job. XML is better for preserving edit structure across modern NLEs. AAF is usually better for audio-heavy handoffs. EDL is old, limited, and surprisingly reliable for simple conforms. There’s no single “best” format, only the least painful one for the task.

7. Should I flatten multicam before exporting XML?

If the receiving editor doesn’t need to switch angles, yes. Flattening trades flexibility for stability, and stability usually wins during handoffs.

8. How long should cleanup take after a good XML import?

For short projects, ten to twenty minutes is normal. For long-form timelines, thirty to sixty minutes isn’t unusual. If you’re rebuilding scenes, something went wrong earlier in the process.

9. What’s the biggest mistake people make with XML?

Expecting perfection. XML is a starting point, not a finish line. The editors who struggle the most are usually the ones expecting it to behave like a full project file.

Get Beyond Your Computer Performance

Run applications on your cloud computer with the latest generation hardware. No more crashes or lags.

Trial includes 1 hour usage + 7 days of storage.

Get Beyond Your Computer Performance

Run applications on your cloud computer with the latest generation hardware. No more crashes or lags.

Trial includes 1 hour usage + 7 days of storage.

Ready to focus on your creativity?

Vagon gives you the ability to create & render projects, collaborate, and stream applications with the power of the best hardware.

Vagon Blog

Run heavy applications on any device with

your personal computer on the cloud.

San Francisco, California

Solutions

Vagon Teams

Vagon Streams

Use Cases

Resources

Vagon Blog

How to Use SolidWorks for 3D Printing: STL Export, Settings & Workflow Guide

How to Use Rhino3D for 3D Printing: A Complete Guide to STL, Meshes, and Printable Geometry

Best VMware Horizon Alternatives for VDI Teams in 2026

Top Citrix Alternatives in 2026

Top Azure Virtual Desktop Alternatives in 2026

Best Laptops of 2026: What Actually Matters

Best 3D Printers in 2026: Honest Picks, Real Use Cases

Best AI Productivity Tools in 2026: Build a Smarter Workflow

Best AI Presentation Tools in 2026: What Actually Works

Vagon Blog

Run heavy applications on any device with

your personal computer on the cloud.

San Francisco, California

Solutions

Vagon Teams

Vagon Streams

Use Cases

Resources

Vagon Blog

How to Use SolidWorks for 3D Printing: STL Export, Settings & Workflow Guide

How to Use Rhino3D for 3D Printing: A Complete Guide to STL, Meshes, and Printable Geometry

Best VMware Horizon Alternatives for VDI Teams in 2026

Top Citrix Alternatives in 2026

Top Azure Virtual Desktop Alternatives in 2026

Best Laptops of 2026: What Actually Matters

Best 3D Printers in 2026: Honest Picks, Real Use Cases

Best AI Productivity Tools in 2026: Build a Smarter Workflow

Best AI Presentation Tools in 2026: What Actually Works

Vagon Blog

Run heavy applications on any device with

your personal computer on the cloud.

San Francisco, California

Solutions

Vagon Teams

Vagon Streams

Use Cases

Resources

Vagon Blog

How to Use SolidWorks for 3D Printing: STL Export, Settings & Workflow Guide

How to Use Rhino3D for 3D Printing: A Complete Guide to STL, Meshes, and Printable Geometry

Best VMware Horizon Alternatives for VDI Teams in 2026

Top Citrix Alternatives in 2026

Top Azure Virtual Desktop Alternatives in 2026

Best Laptops of 2026: What Actually Matters

Best 3D Printers in 2026: Honest Picks, Real Use Cases

Best AI Productivity Tools in 2026: Build a Smarter Workflow

Best AI Presentation Tools in 2026: What Actually Works

Vagon Blog

Run heavy applications on any device with

your personal computer on the cloud.

San Francisco, California

Solutions

Vagon Teams

Vagon Streams

Use Cases

Resources

Vagon Blog