Instant Connection for Pixel Streaming

— New Feature Automated Setup

Top Movies Created Using Blender

Top Movies Created Using Blender

Top Movies Created Using Blender

Published on January 29, 2026

Table of Contents

Blender films aren’t “good for a free tool” anymore. They’re winning major awards, showing up in serious film conversations, and proving that small teams with sharp taste can compete with studios that have entire buildings full of hardware. If you’re still thinking of Blender as a stepping stone instead of a destination, you’re already behind.

Let’s start with the film that made that impossible to ignore.

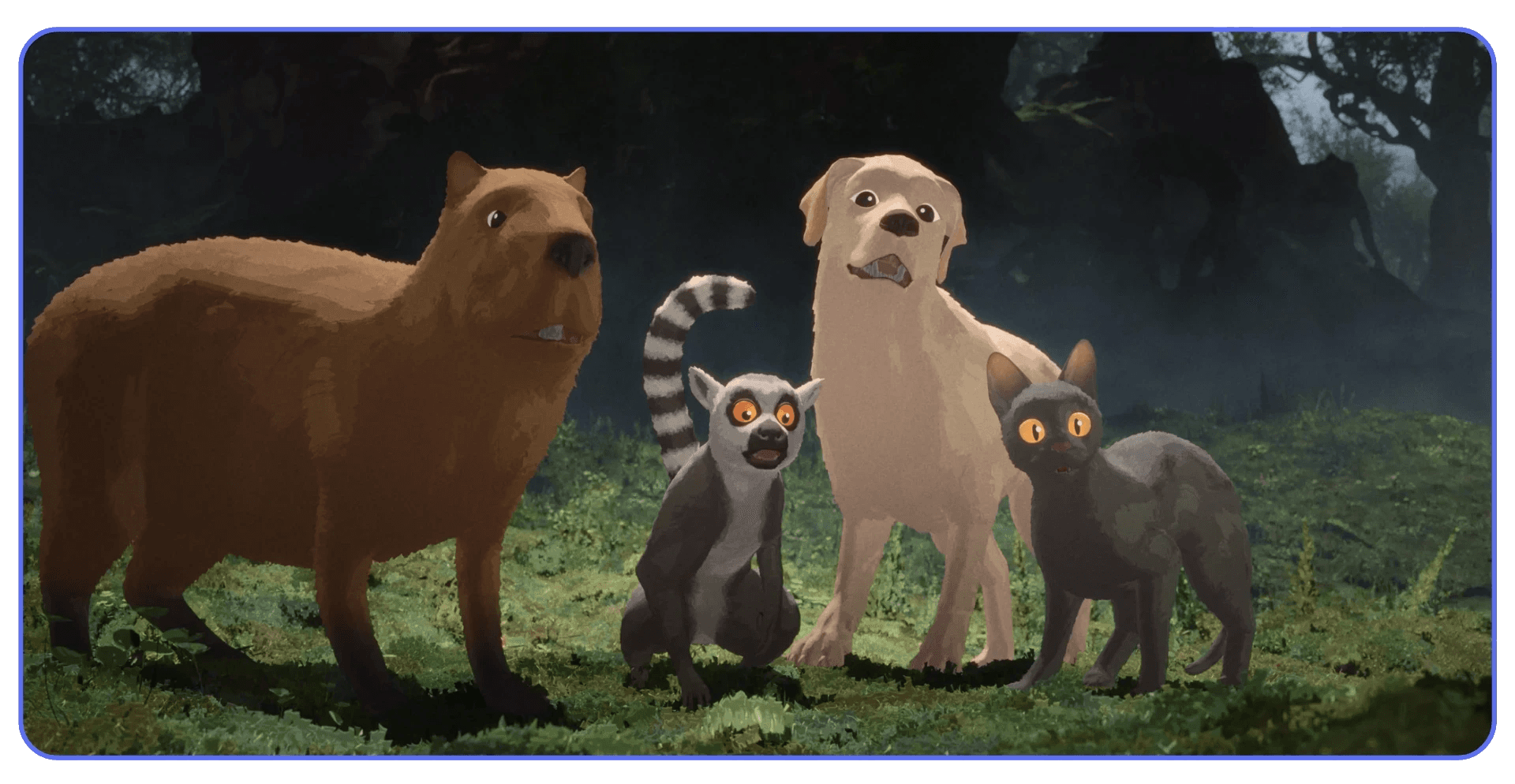

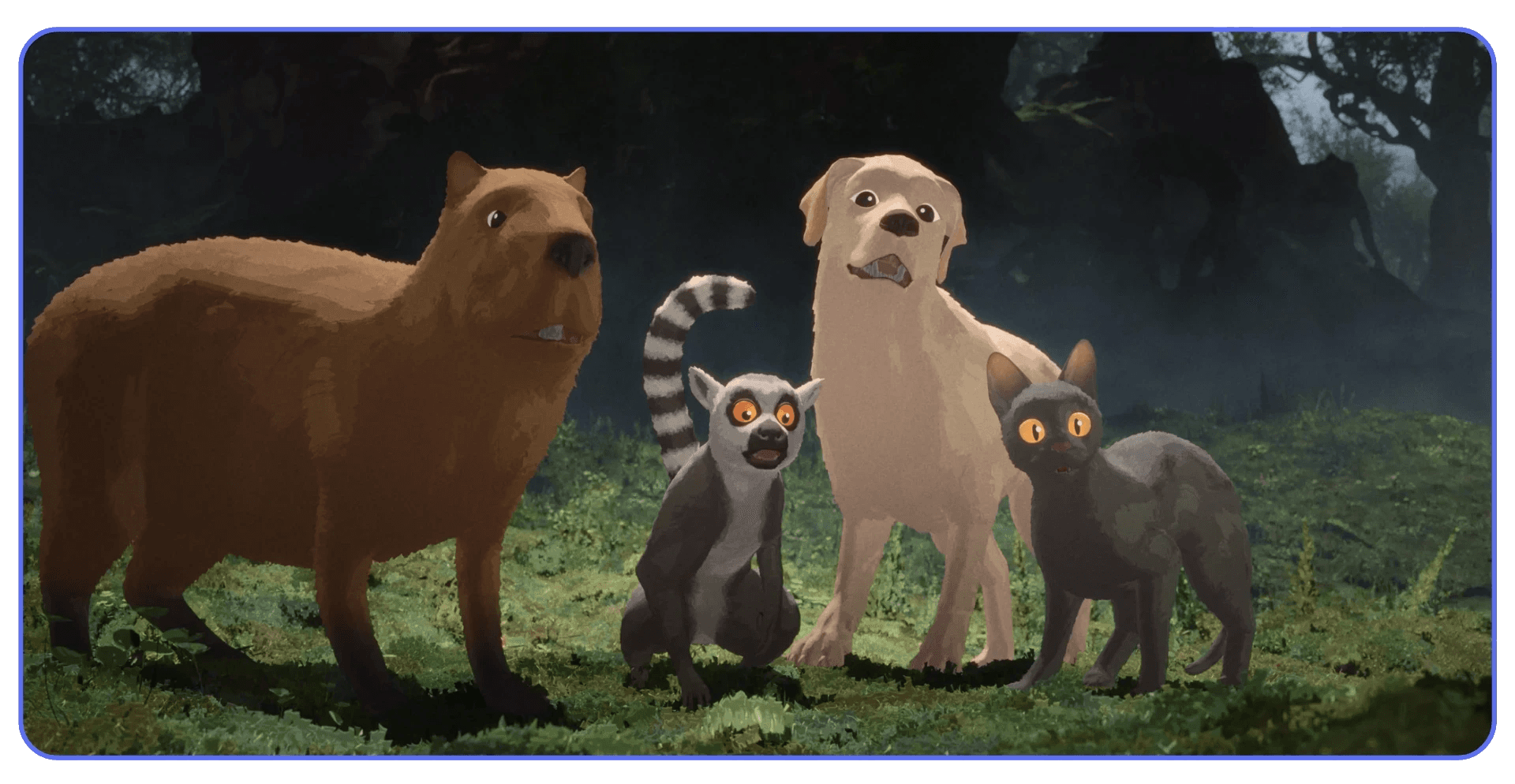

#1. Flow (2024)

This is the one that changed the conversation.

Flow isn’t impressive because it was made with Blender. It’s impressive because it trusts visual storytelling more than most big-budget animated films do. No dialogue. No frantic exposition. Just movement, pacing, and composition doing the work. And it worked well enough to win major international awards and force a lot of people to recalibrate their assumptions.

What struck me watching Flow wasn’t technical bravado. It was restraint. The environments are detailed but never noisy. Animation is purposeful, not flashy. Camera moves feel deliberate, like someone actually thought about why the camera should move at all. That’s a harder skill than adding another layer of polish.

From a Blender perspective, this film quietly demolishes a common excuse. You don’t need exotic shaders or bleeding-edge simulations to make something that lands emotionally. You need clarity. Clean layouts. Consistent lighting logic. Scenes that render because they were designed to render, not because someone brute-forced them into submission.

I’ve noticed a lot of Blender artists obsess over surface detail and forget rhythm. Flow does the opposite. It lets shots breathe. It allows silence. It trusts the audience. That’s a directing decision, not a software feature.

If there’s a lesson here, it’s not “Blender can do this too.” It’s that finishing a focused film with strong taste beats endlessly refining a technically ambitious one. Every time.

And that makes the rest of this list make a lot more sense.

If you are experimenting with using Blender on an iPad, it’s a great way to sketch ideas and block shots early, but heavier scenes will still demand more power later in production.

#2. Plumíferos (2008)

This one doesn’t look modern. And that’s exactly why it matters.

Plumíferos was the first full-length animated feature made entirely with Blender. Not a short. Not an experiment. A real feature film, finished and released at a time when Blender was still fighting to be taken seriously at all. If you judge it purely by today’s visual standards, you’ll miss the point completely.

What Plumíferos proved was pipeline discipline. Scenes were planned because they had to be. Assets were reused because they couldn’t afford not to. Lighting was simplified because render times were already brutal by 2008 standards. None of this was stylistic minimalism. It was survival. And honestly, that constraint probably saved the project.

This is where a lot of modern Blender users get it backwards. They assume early projects were “simple” because the tools were weak. In reality, the teams were just ruthless about scope. They made decisions early and lived with them. No endless tweaking. No last-minute lighting overhauls. No “I’ll fix it in the next render.”

Does it show its age? Of course. Facial rigs are stiff in places. Shading is basic. But the film exists. That already puts it ahead of thousands of unfinished Blender features sitting on hard drives right now.

If you’re planning a long-form Blender project, Plumíferos is a quiet warning. Ambition is fine. Indecision is deadly. This film got finished because the creators respected their limits and committed early. That lesson hasn’t aged a day.

If you are exploring 2D animation in Blender, especially for storyboards or animatics, it can help you solve pacing and performance long before committing to full 3D scenes.

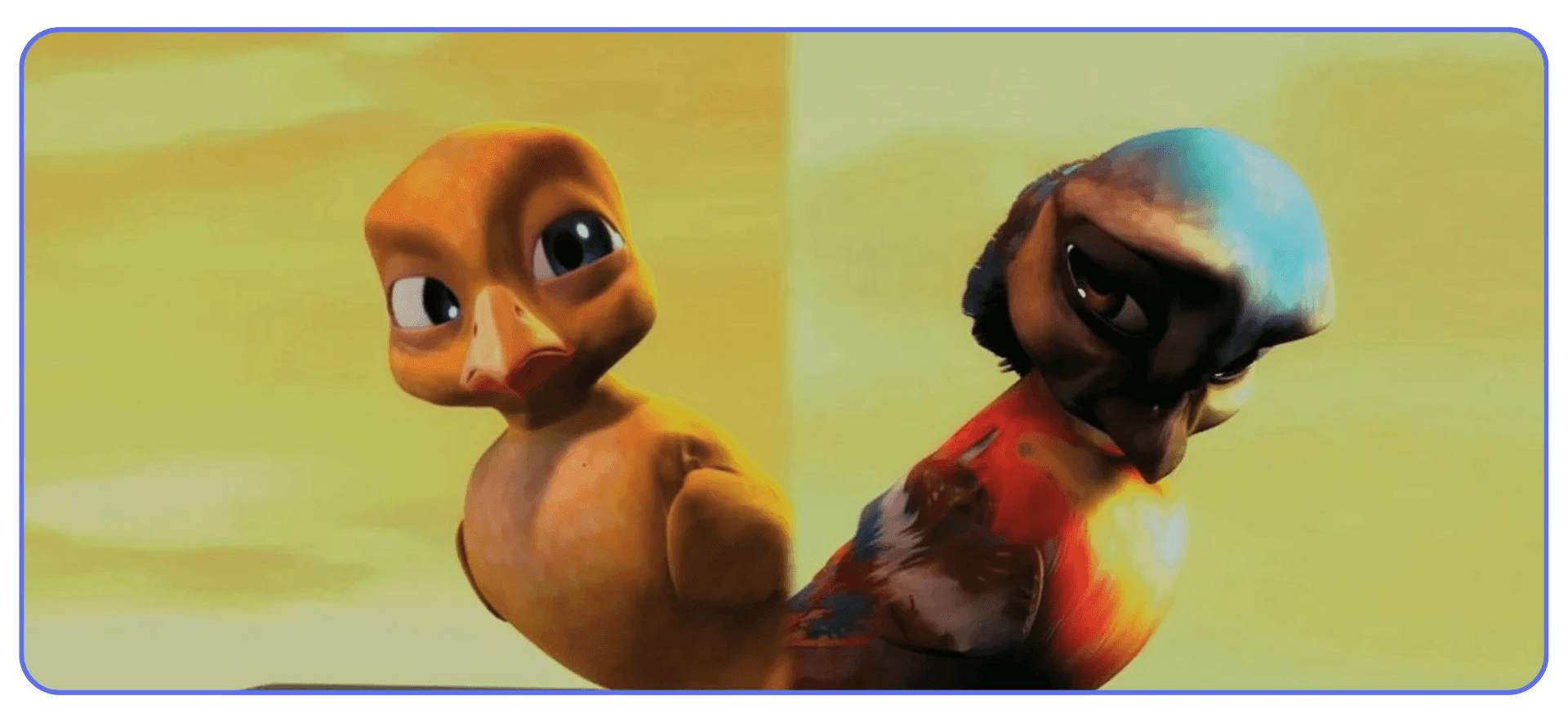

#3. Tears of Steel (2012)

This is where Blender stopped being boxed into animation.

Tears of Steel mixed live-action footage with heavy CGI at a time when most people still assumed Blender couldn’t handle serious VFX work. Motion tracking, compositing, environment extensions, digital characters. All done inside Blender, with the goal of stress-testing the software in real production conditions.

Some of it holds up surprisingly well. Some of it doesn’t. And that’s fine.

What still works is the integration. The way CG elements sit in real plates without constantly screaming for attention. The lighting matches more often than it misses. The camera tracking is solid enough that you stop thinking about the tech and start watching the scene. That’s the real win.

What shows its age is mostly aesthetic. Certain materials feel dated. Some animations are stiff. But those issues aren’t Blender-specific. You see the same thing in plenty of studio VFX from that era.

For Blender users, this project delivered a different kind of confidence. It showed that Blender wasn’t just for stylized worlds or contained environments. You could take it on set, bring footage back, and actually finish shots that had to match reality. That opened doors for indie filmmakers who couldn’t justify expensive VFX pipelines.

The deeper lesson here is about ambition management. Tears of Steel aimed high, but it was structured like a test lab, not a passion project spiraling out of control. Every shot had a purpose. Every technical challenge fed back into the tool itself.

If you’ve ever wanted to use Blender for live-action VFX, this film is still a reference. Not because it’s perfect, but because it proved the workflow was real.

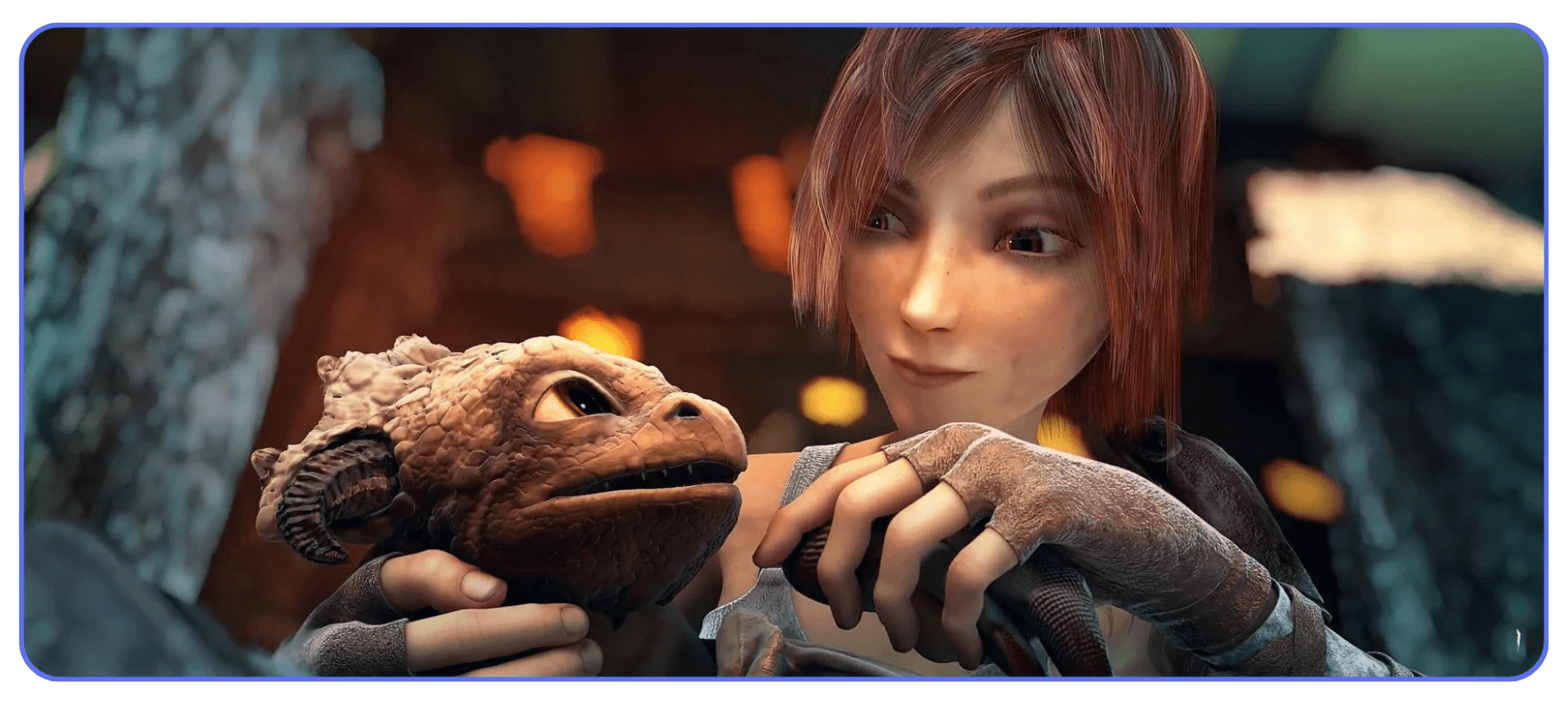

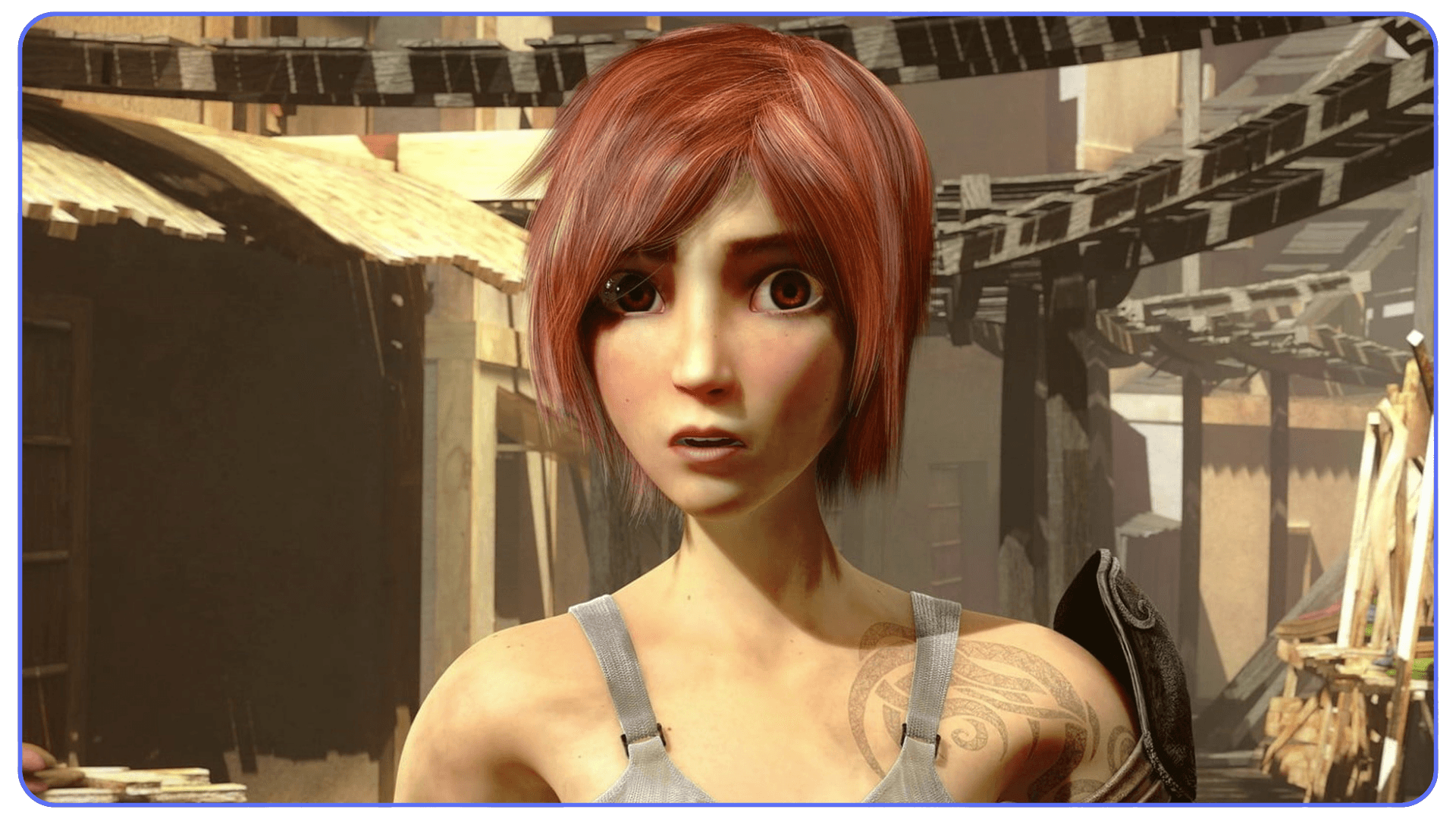

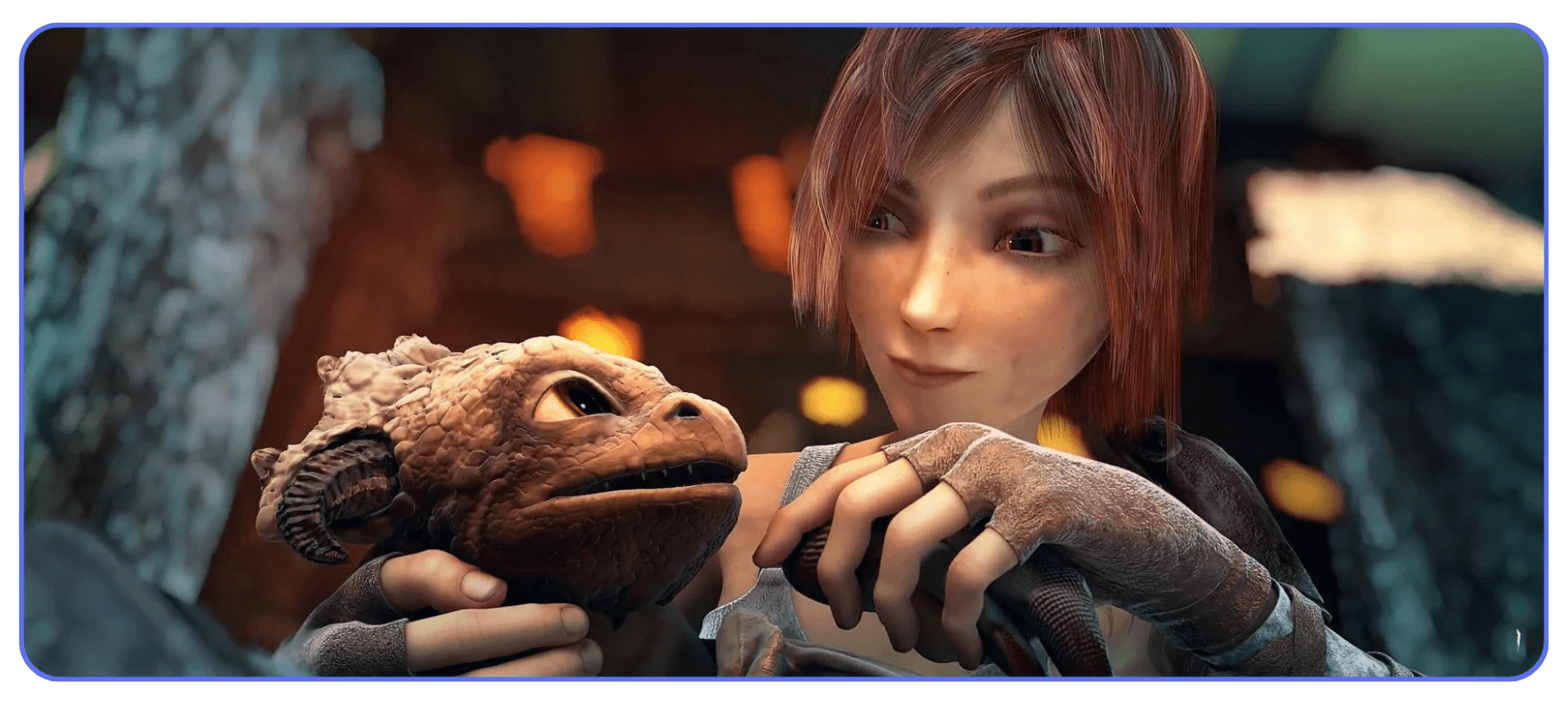

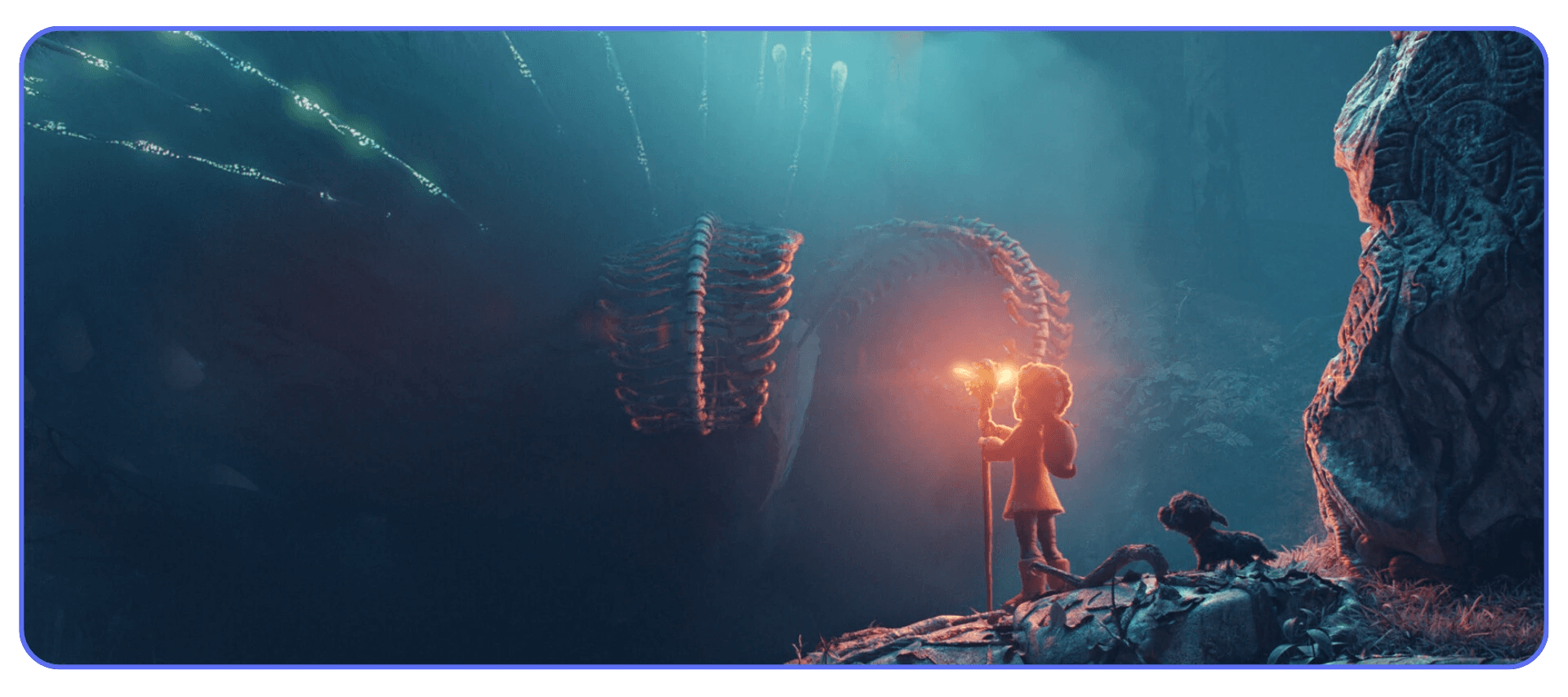

#4. Sintel (2010)

This is the one people keep coming back to. And it’s not because of the tech.

Sintel works because it understands something a lot of Blender projects miss. Emotion carries weight when everything else gets out of the way. The story is simple, almost blunt, but every choice supports it. Camera placement is calm. Cuts are motivated. Lighting does most of the storytelling heavy lifting.

Technically, there’s nothing here that feels flashy by today’s standards. No simulation overload. No shader gymnastics. But the atmosphere still holds. Snow feels cold. Fire feels dangerous. Distance feels lonely. Those are lighting and composition decisions, not node tricks.

I’ve seen people try to recreate Sintel by copying materials or render settings, and it almost always misses the point. The look comes from planning. From knowing what time of day a scene lives in. From committing to a mood early and protecting it all the way through production.

What makes Sintel endure is focus. It never tries to be clever. It never shows off for its own sake. It just tells the story it set out to tell, cleanly and with confidence.

For Blender users, this short is still one of the best reminders that storytelling problems don’t get solved in the shader editor. They get solved on paper, before you open the file.

If you are constantly tweaking render settings to save time, it’s worth remembering that optimization helps most when scenes are designed with rendering in mind from the start.

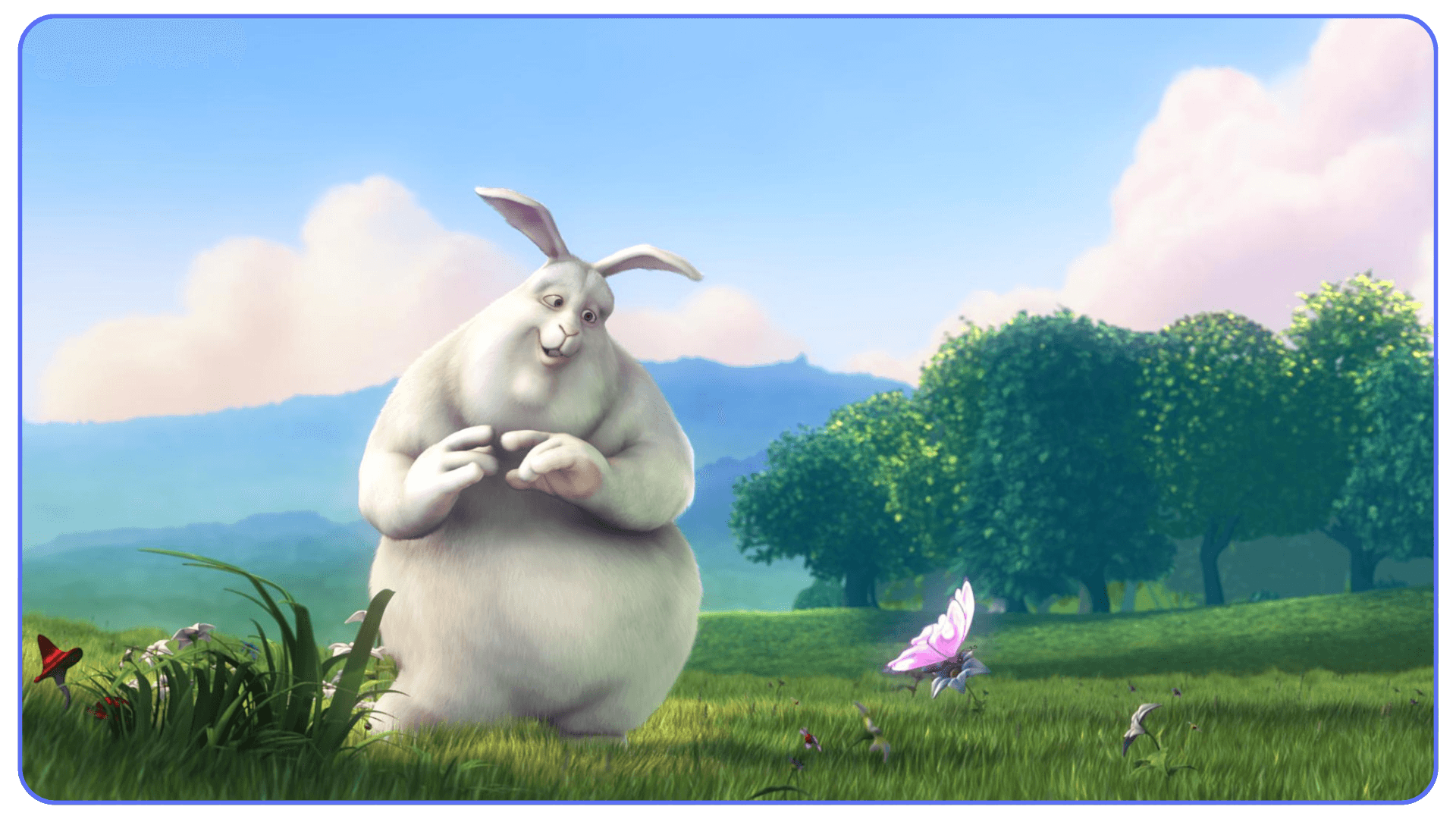

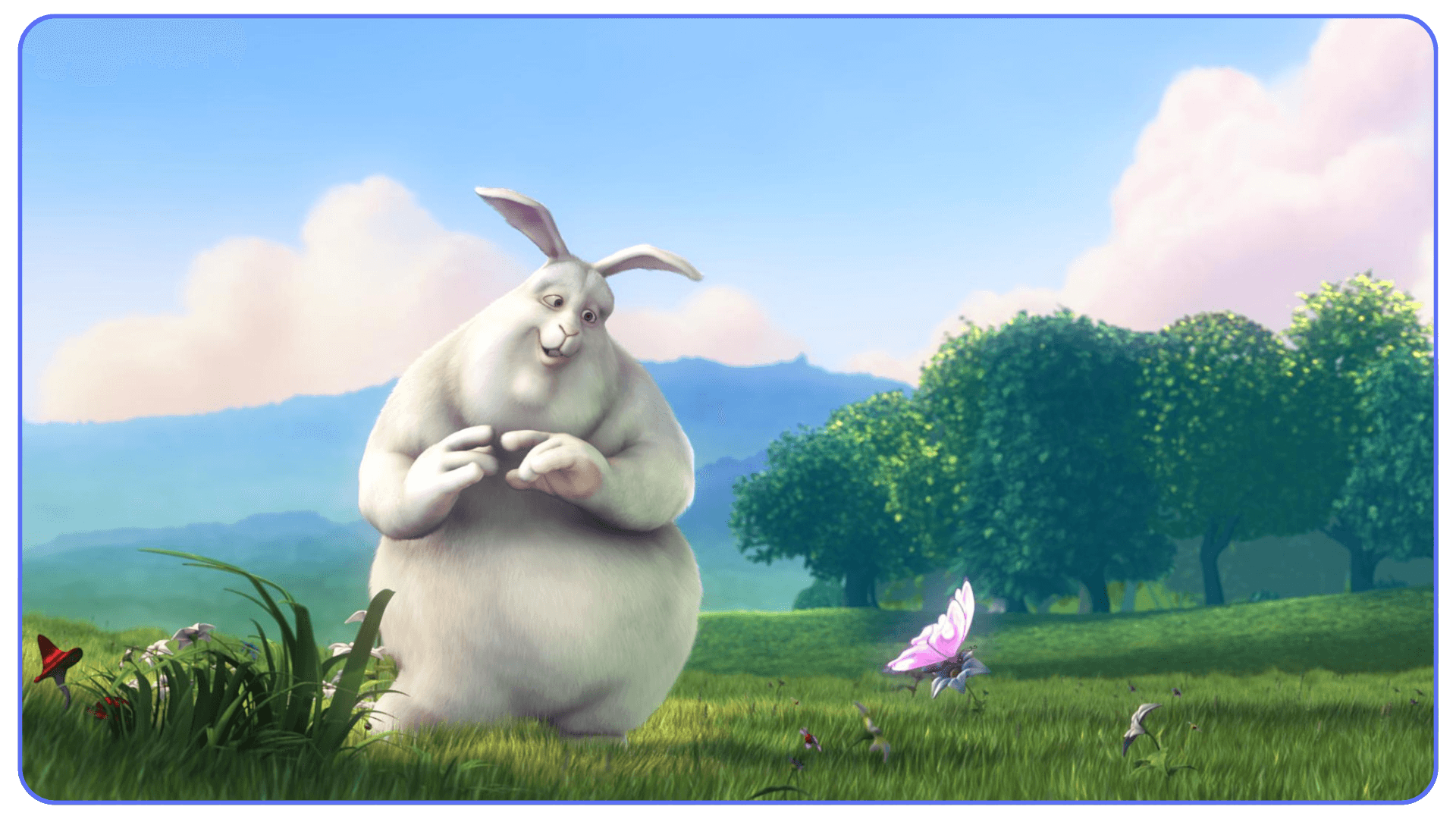

#5. Big Buck Bunny (2008)

Comedy is brutal in 3D. Big Buck Bunny understood that early.

On the surface, this short looks playful and simple. Underneath, it’s doing a lot of heavy lifting. Exaggerated animation, clear silhouettes, readable expressions, and timing that has to land exactly right or the joke dies. There’s nowhere to hide when something isn’t funny.

From a Blender standpoint, this project pushed character animation hard for its time. Fur, skin deformation, squash and stretch, facial performance. All of it had to work together, shot after shot. And because the tone is light, mistakes stand out even more. You notice every awkward pause. Every stiff movement.

What I think made Big Buck Bunny so effective as a learning tool is that it exposed weaknesses immediately. If an animation beat was off, everyone could see it. If lighting flattened a character, the humor collapsed. That kind of feedback loop is priceless when you’re learning.

A lot of Blender artists still underestimate comedy. They chase realism or mood because those feel safer. Big Buck Bunny shows that clarity and timing are harder skills. And once you have those, everything else gets easier.

This short didn’t just entertain. It trained an entire generation of Blender animators to think about performance first. That’s a legacy that still matters.

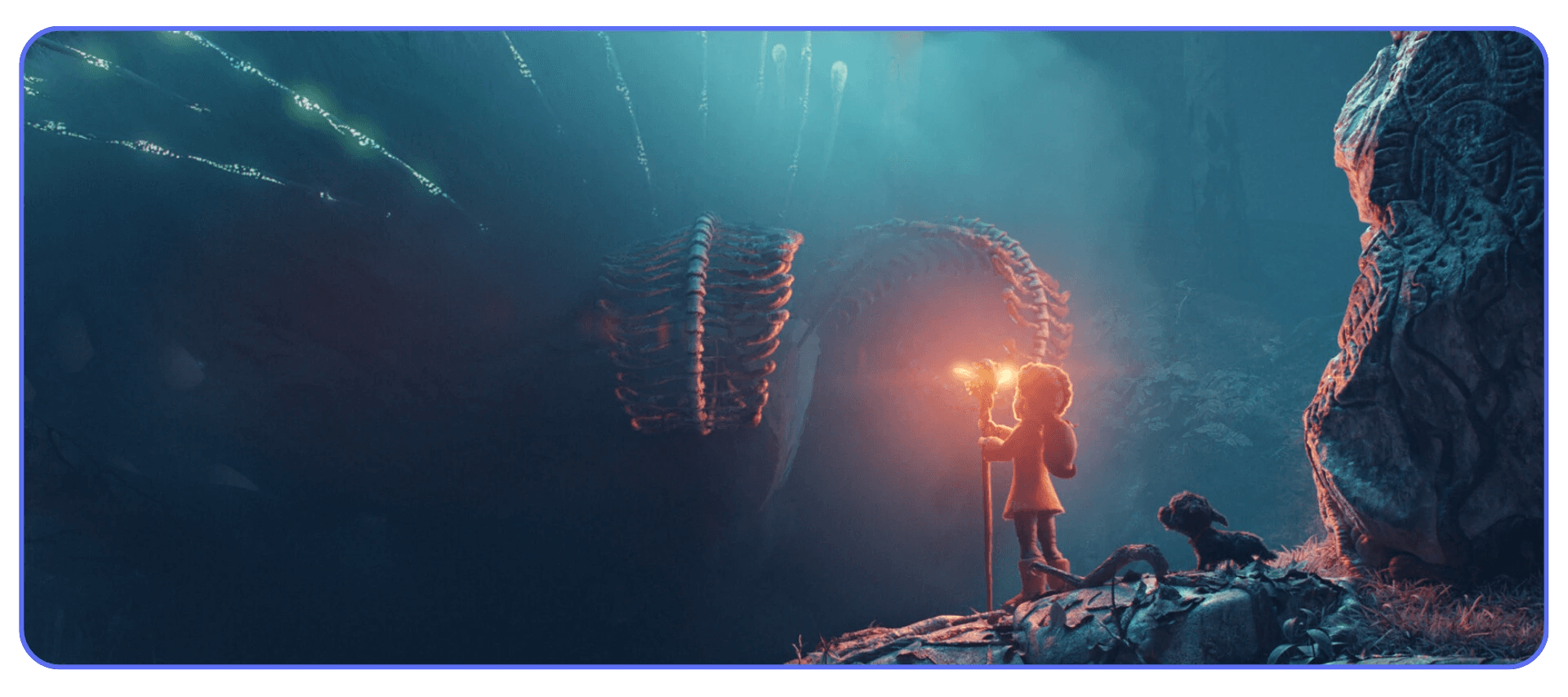

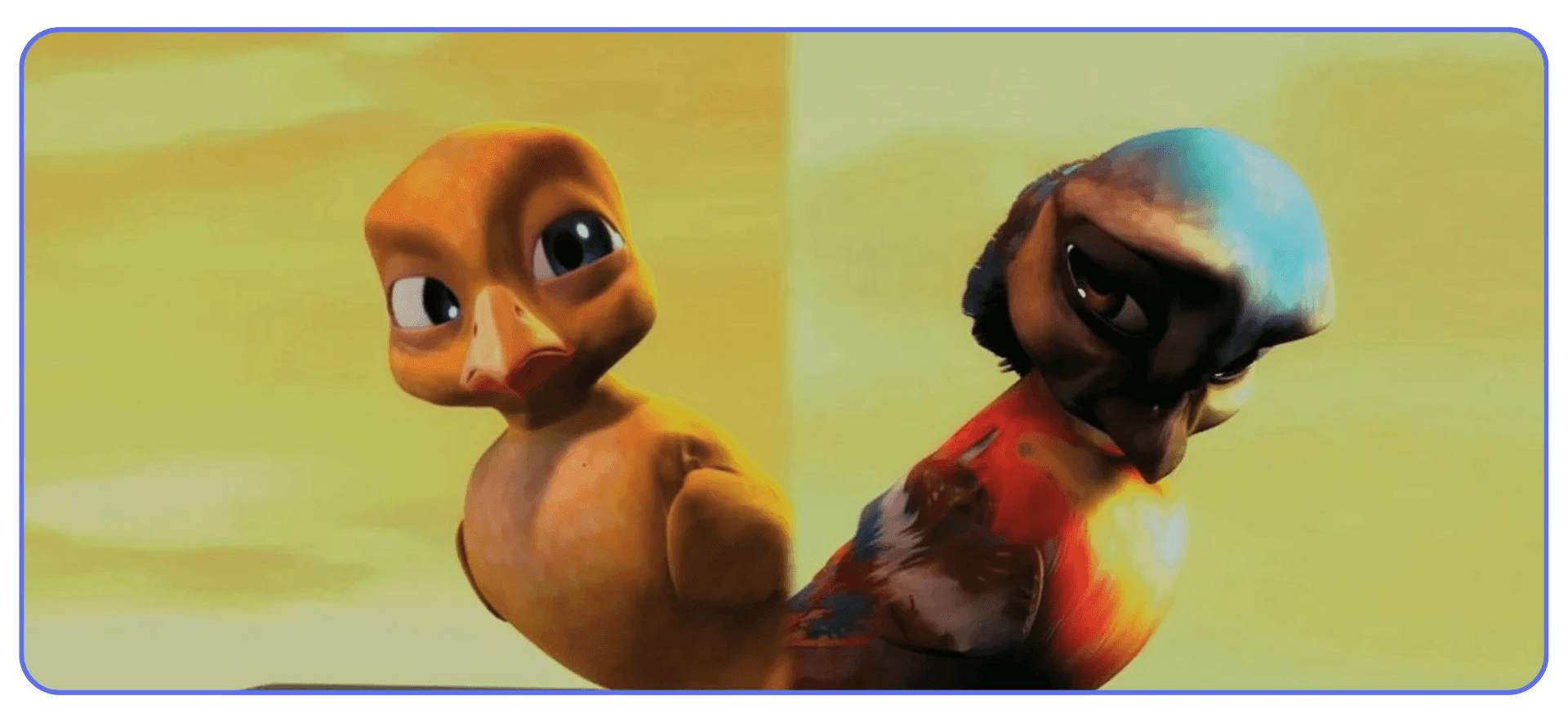

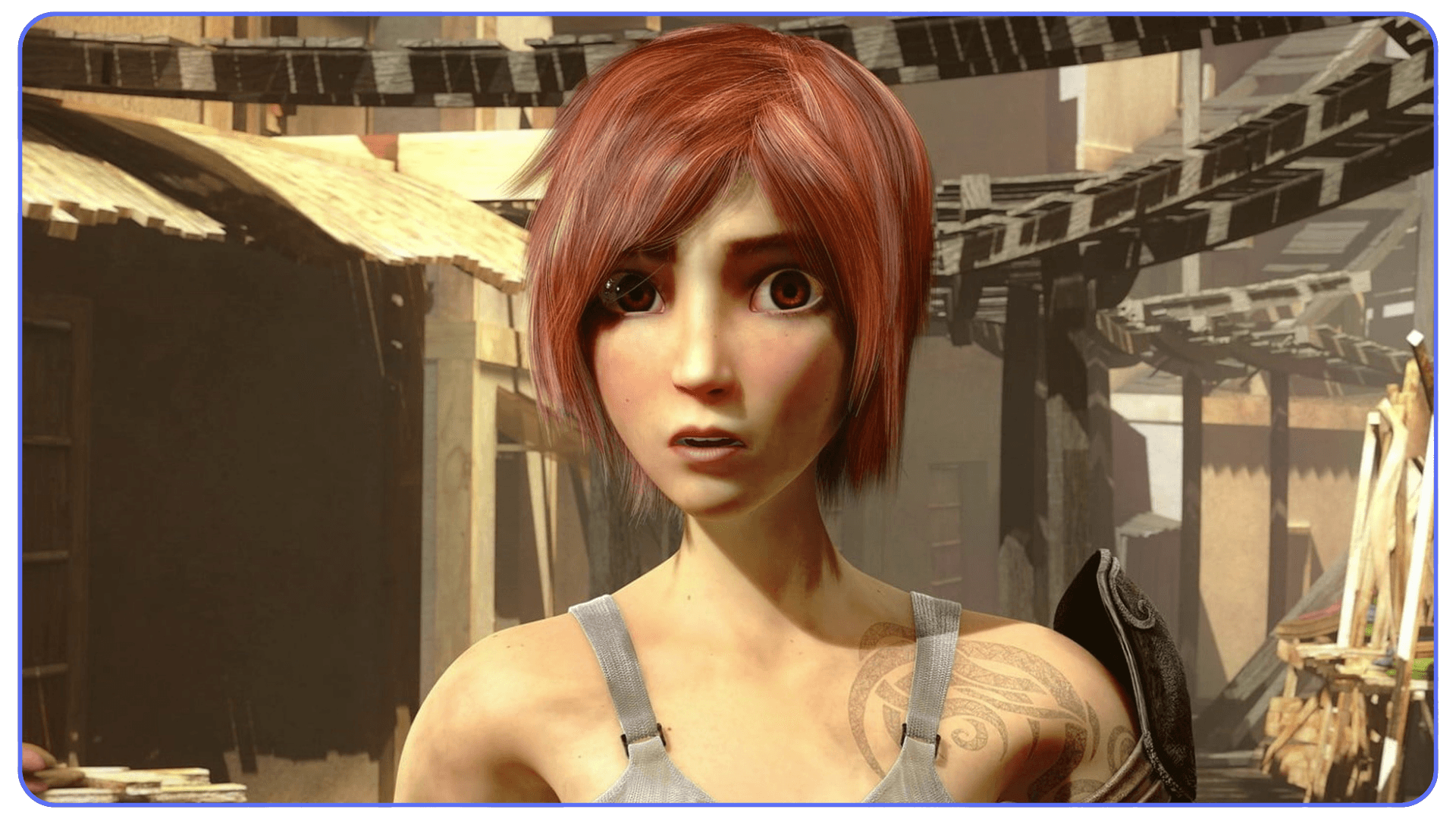

#6. Spring (2019)

This is the short a lot of Blender users admire quietly and rarely talk about.

Spring looks simple at first glance. Soft colors. Gentle motion. Minimal dialogue. But that calm surface hides a huge amount of deliberate decision-making. Every shot is composed like a painting. Every movement feels measured. Nothing rushes.

What stands out here is restraint. The environments aren’t overloaded. Textures aren’t screaming for attention. Animation is subtle, almost reserved. That takes confidence. It’s much easier to add detail than to remove it and trust the result.

From a production standpoint, Spring is a masterclass in mood control. Lighting stays consistent across scenes. Color palettes are limited and intentional. Even small camera moves feel planned rather than reactive. This is the kind of discipline that usually comes from experience, not tutorials.

I think Spring feels even more relevant now than it did at release. There’s been a noticeable shift toward quieter, more atmospheric animation in recent years, especially in indie work. This short anticipated that trend instead of chasing spectacle.

For Blender artists, Spring is a reminder that not every project needs to shout. Sometimes the strongest choice is to lower the volume and let the audience lean in.

If you are trying to speed up your workflow, learning essential Blender shortcuts and hotkeys can make iteration feel lighter and keep momentum alive during long projects.

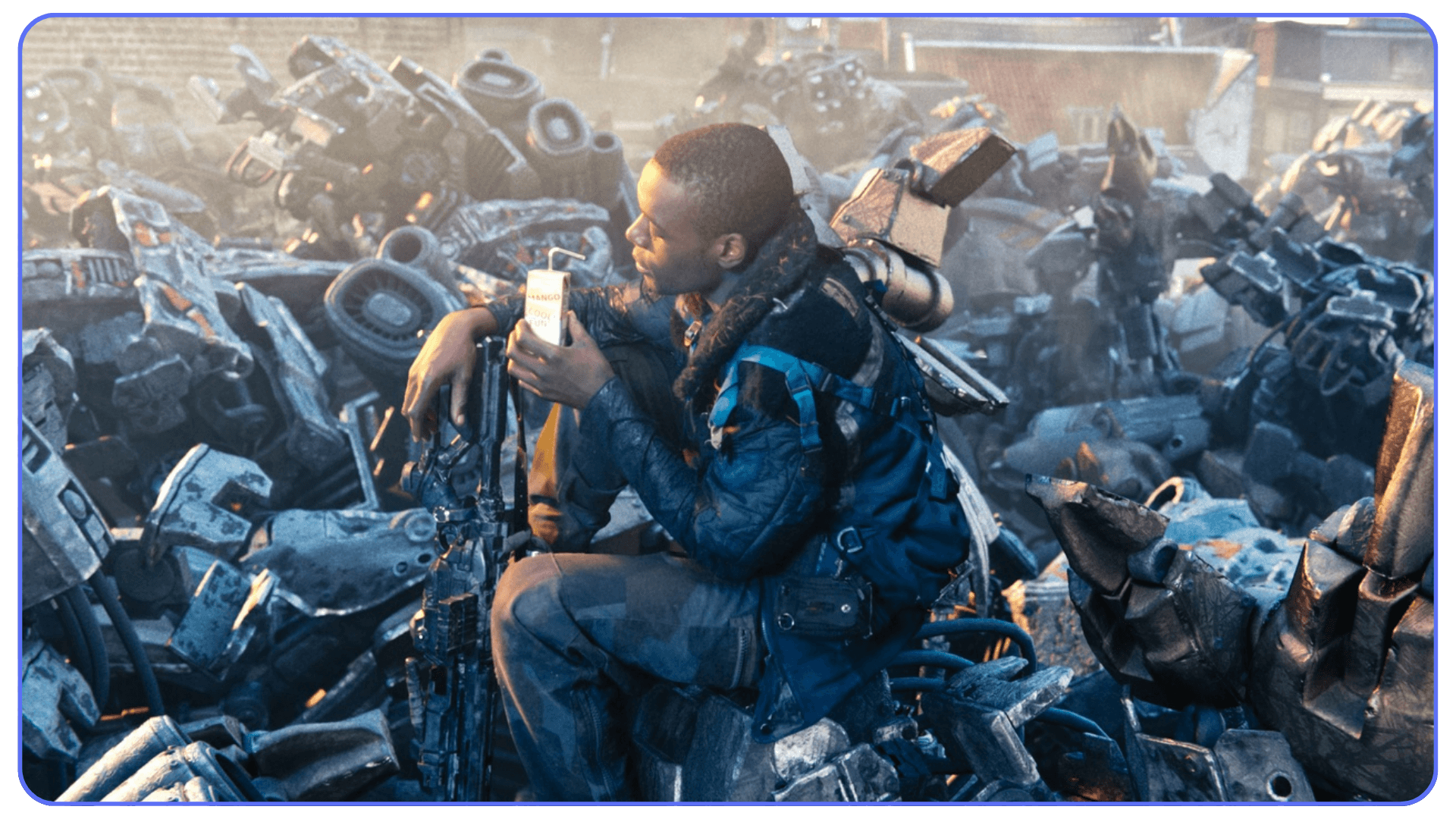

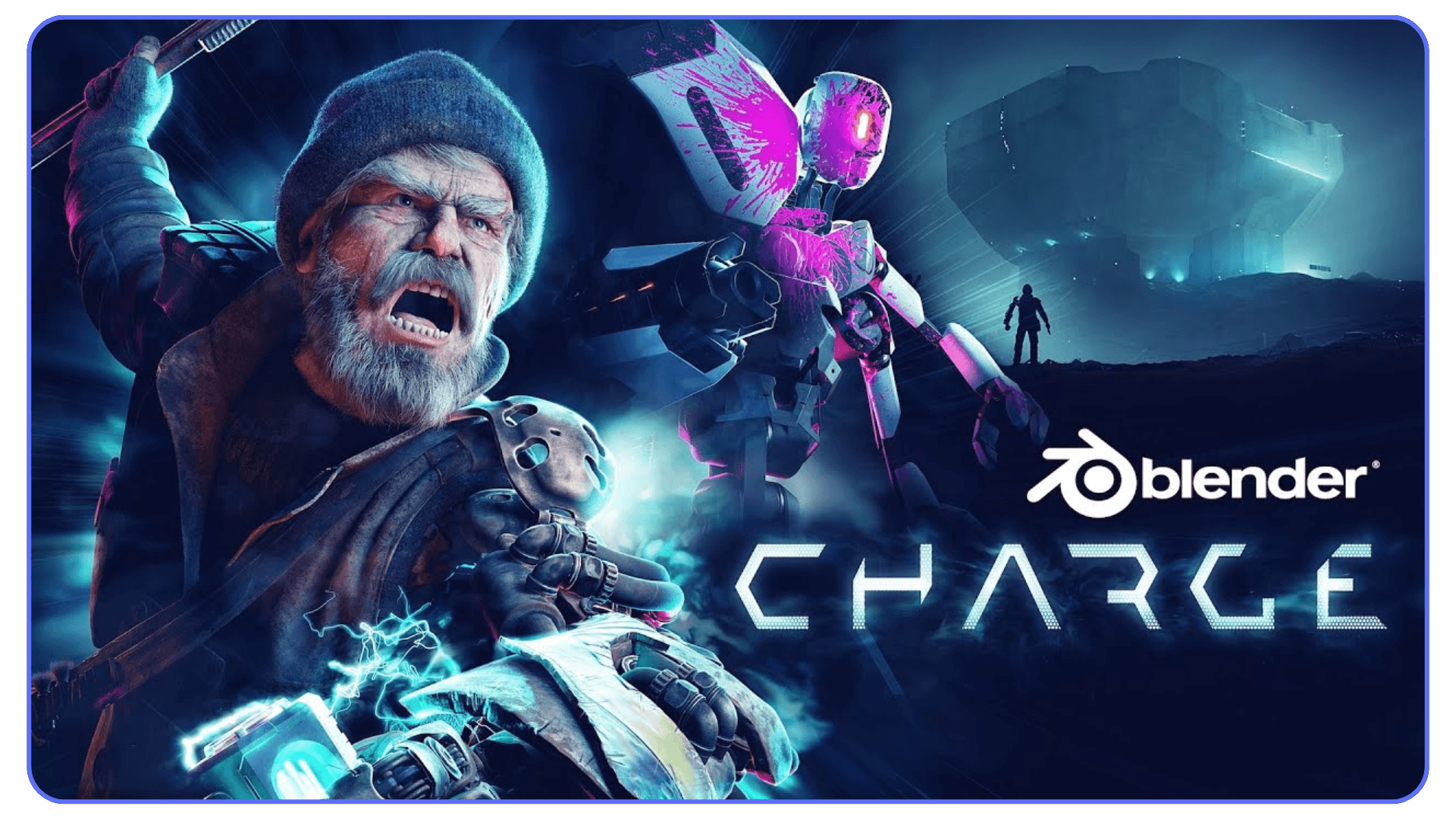

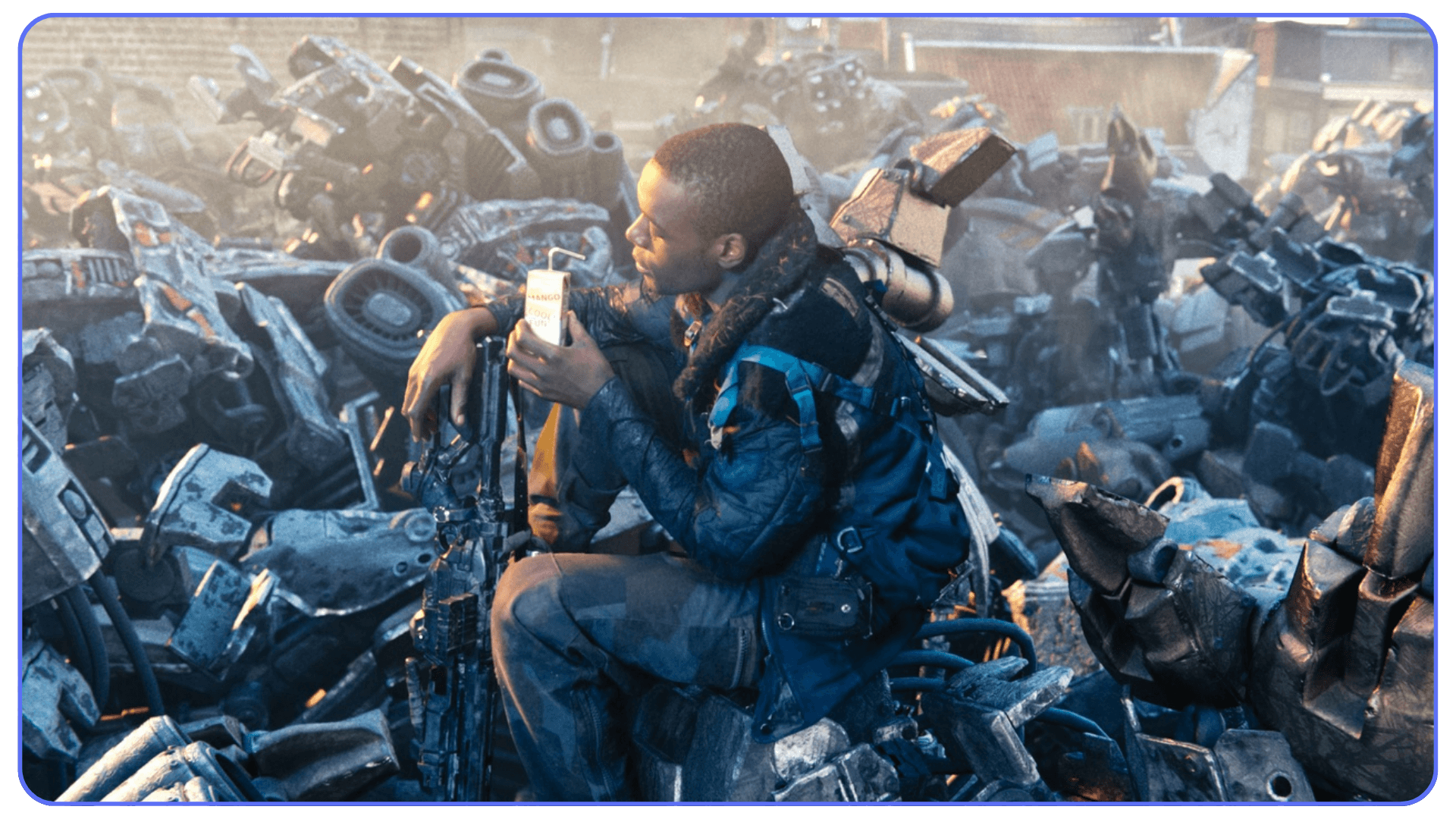

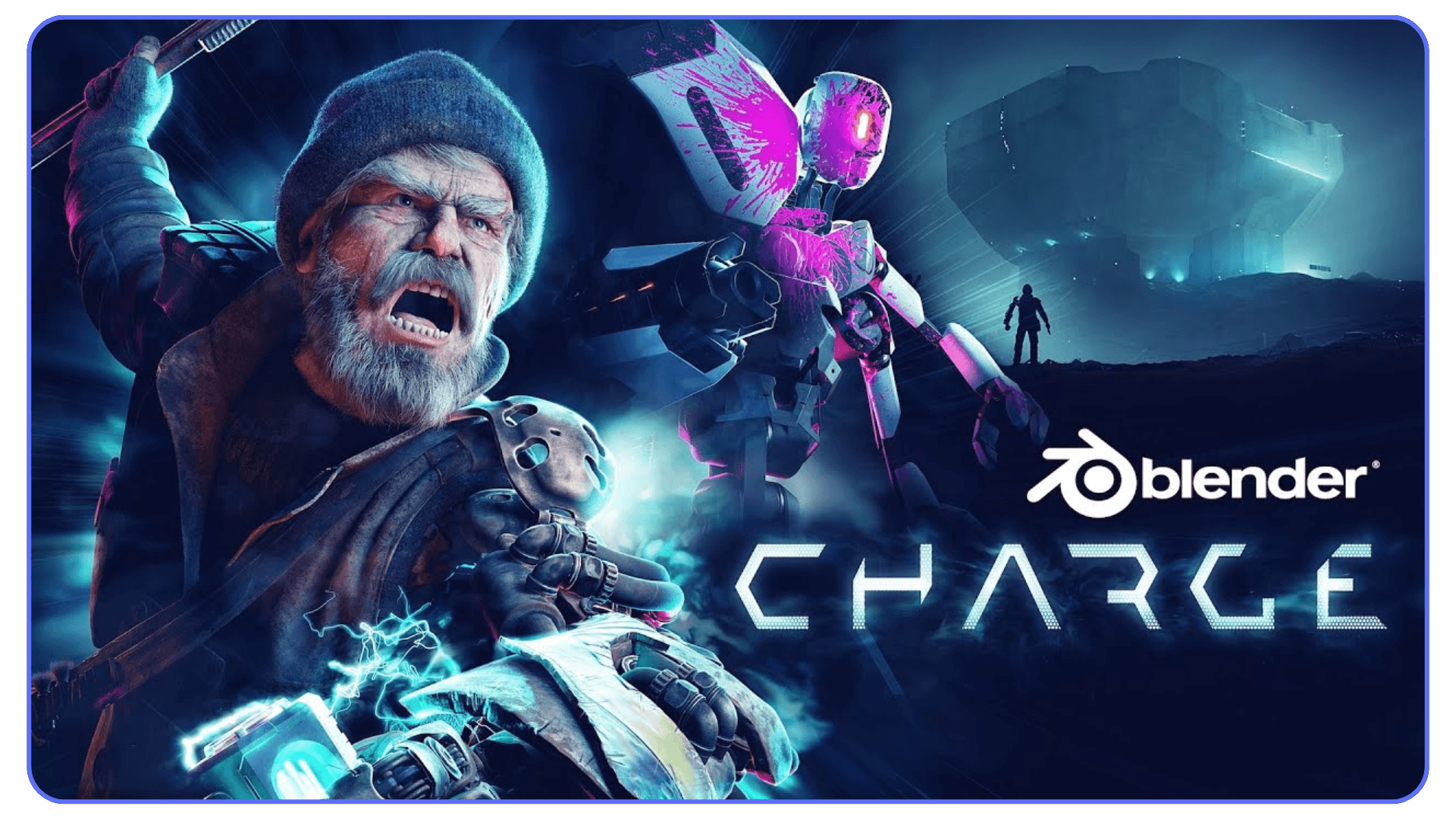

#7. Charge (2022)

This is what modern Blender production actually looks like.

Charge doesn’t feel like an experiment or a tech demo. It feels like a small studio project with real constraints and real deadlines. Assets are dense. Environments are complex. Lighting setups are layered. And yet the film stays readable, which is harder than it sounds.

What stands out here is how contemporary the pipeline feels. You can sense the balance between quality and practicality in every shot. Nothing feels accidental. Scenes are built to survive iteration without collapsing under their own weight. That’s a skill a lot of Blender users only learn the hard way.

There’s also a noticeable confidence in how effects are used. Explosions, debris, motion blur. They support the action instead of hijacking it. That restraint again. It keeps showing up in the strongest Blender films for a reason.

If you’ve worked on a serious Blender project recently, Charge will feel familiar. The tradeoffs. The compromises. The constant negotiation between ambition and render time. This short doesn’t pretend those problems don’t exist. It works around them.

As a reference, Charge is valuable because it reflects current reality. Not nostalgia. Not future promises. Just what Blender can do right now when it’s used with intent.

What These Blender Films All Get Right

None of these films succeeded because they pushed every Blender feature to its limit. They succeeded because they made decisions early and defended them.

Storyboards came first. Not as a formality, but as a filter. If a shot didn’t serve the story or the rhythm, it didn’t survive. Lighting wasn’t an afterthought. It was part of the narrative language, locked in before assets spiraled out of control. Scope stayed intentional. Not small, just controlled.

There’s also a shared respect for clarity. You always know where to look. You always understand what matters in the frame. That sounds obvious until you watch unfinished Blender projects that drown the viewer in detail without direction.

I’ve noticed that the best Blender films treat limitations like design constraints, not obstacles. Render time, hardware limits, team size. All of it shapes smarter creative choices instead of sabotaging them. That mindset shows up in every finished frame.

This isn’t about talent gaps. It’s about discipline. And discipline is what most personal Blender projects quietly lack.

If you are using Blender on a Chromebook, cloud-based setups become especially relevant once your scenes outgrow what local hardware can comfortably handle.

Where Most Blender Film Projects Still Break Down

This is the part nobody likes to talk about.

Most Blender film projects don’t fail because the idea was bad or the artist wasn’t skilled enough. They stall because complexity creeps in quietly and then refuses to leave. One extra prop here. One more light there. A “quick” simulation that turns into a permanent render tax.

Late in production, scenes get heavy. Renders slow down. Simple tweaks suddenly take hours to preview. That’s when motivation drops. You stop experimenting because every change feels expensive. And once iteration slows, the project starts to freeze in place.

Hardware plays a bigger role here than people admit. Not because you need the latest GPU, but because waiting kills momentum. When lighting tweaks take all night to render, you stop refining lighting. When animation previews lag, timing suffers. These are creative problems caused by technical friction.

Burnout usually follows. Not dramatic burnout. The quiet kind. You open the project less often. Weeks pass. Eventually, it becomes “that film I’ll finish someday.”

Every filmmaker on this list avoided that trap by respecting production reality early. They didn’t wait for perfect conditions. They built workflows that allowed them to keep moving. That’s the difference between a finished film and a folder full of versions.

If you are unsure which Blender render engines to use, the right choice often depends less on trends and more on how early you lock lighting and scope decisions.

Where Vagon Cloud Computer Fits Into Blender Filmmaking

At some point, Blender projects stop being limited by ideas and start being limited by hardware. Scenes get heavier. Lighting setups multiply. Simulations creep in. Even small tweaks begin to cost real time, not seconds, but hours. That’s usually when momentum starts to slip.

This is exactly where Vagon Cloud Computer makes sense for Blender filmmakers. Instead of forcing your project to fit the limits of a local machine, you move the heavy work to a high-performance cloud environment. No new hardware purchases. No underclocking your ambition just to keep renders manageable.

What matters most here isn’t raw render speed. It’s iteration speed. With Vagon, complex Blender scenes remain interactive, lighting changes are easier to test, and animation previews don’t feel like a punishment. That freedom encourages better decisions, because you can actually afford to explore them.

Vagon is especially useful for short films and feature projects where visual complexity ramps up late in production. Final lighting passes, effects-heavy sequences, dense environments. The stages where local machines often become a bottleneck. Instead of locking scenes too early or avoiding changes altogether, you stay flexible longer.

It’s not something every Blender user needs. Simple scenes and learning projects run just fine locally. But when a film’s scope grows and iteration time starts shaping creative choices, Vagon Cloud Computer stops being a convenience and becomes part of a sustainable workflow.

Final Thoughts

If there’s a common thread running through all these films, it’s not software tricks or technical flexing. It’s taste. Clear priorities. And a willingness to commit to decisions early, then live with them.

Blender is already capable. That question is settled. What still separates finished films from abandoned ones is whether the workflow supports momentum or slowly drains it. When iteration stays fast, ideas stay alive. When it doesn’t, even great concepts start to shrink.

Tools like Vagon Cloud Computer don’t replace skill or vision. They remove friction at the exact moment friction becomes dangerous. Late production. Heavy scenes. Big decisions that still need room to breathe. Used thoughtfully, that support can be the difference between polishing a film and shelving it.

The real takeaway is simple, even if it’s uncomfortable. Finishing matters more than perfection. Infrastructure should serve creativity, not quietly steer it. And the Blender films people remember are almost always the ones where someone chose progress over endless tweaking.

Blender isn’t the underdog anymore. The question now is what you do with that freedom.

FAQs

1. Can Blender really be used for professional films today?

Yes. That debate is basically over. Blender is already being used for award-winning shorts, full-length animated features, and serious VFX work. The limiting factor now isn’t the software. It’s planning, taste, and whether the production pipeline can actually support the project through the finish line.

2. Do I need a powerful local machine to make a Blender film?

Not at the beginning. Early stages like storyboarding, blocking, and rough animation run fine on modest hardware. Problems usually appear later, when scenes get dense and lighting, effects, and final renders stack up. That’s where many projects slow down or stall.

3. Why do so many Blender film projects get abandoned?

Most don’t fail because of lack of skill. They fail because iteration becomes too slow. When testing changes takes hours instead of minutes, creators stop experimenting. Momentum drops. Motivation follows. Over time, the project quietly fades out.

4. When does using Vagon Cloud Computer make sense for Blender users?

Vagon is most useful once projects move beyond simple scenes. Short films with complex lighting, feature projects, heavy environments, or late-stage polish where local machines become a bottleneck. It’s not necessary for every Blender user, but it becomes valuable when iteration speed starts shaping creative choices.

5. Will using cloud computers replace local workflows?

No. Most Blender filmmakers still use local machines for daily work. Cloud systems complement that setup. You bring in extra power when you need it, instead of forcing every project to fit your weakest hardware limit.

6. What’s the biggest lesson from successful Blender films?

Finish. Plan early. Respect constraints. And protect your ability to iterate. The films people remember aren’t the ones with the most complex shaders. They’re the ones that made clear decisions and followed through.

Blender films aren’t “good for a free tool” anymore. They’re winning major awards, showing up in serious film conversations, and proving that small teams with sharp taste can compete with studios that have entire buildings full of hardware. If you’re still thinking of Blender as a stepping stone instead of a destination, you’re already behind.

Let’s start with the film that made that impossible to ignore.

#1. Flow (2024)

This is the one that changed the conversation.

Flow isn’t impressive because it was made with Blender. It’s impressive because it trusts visual storytelling more than most big-budget animated films do. No dialogue. No frantic exposition. Just movement, pacing, and composition doing the work. And it worked well enough to win major international awards and force a lot of people to recalibrate their assumptions.

What struck me watching Flow wasn’t technical bravado. It was restraint. The environments are detailed but never noisy. Animation is purposeful, not flashy. Camera moves feel deliberate, like someone actually thought about why the camera should move at all. That’s a harder skill than adding another layer of polish.

From a Blender perspective, this film quietly demolishes a common excuse. You don’t need exotic shaders or bleeding-edge simulations to make something that lands emotionally. You need clarity. Clean layouts. Consistent lighting logic. Scenes that render because they were designed to render, not because someone brute-forced them into submission.

I’ve noticed a lot of Blender artists obsess over surface detail and forget rhythm. Flow does the opposite. It lets shots breathe. It allows silence. It trusts the audience. That’s a directing decision, not a software feature.

If there’s a lesson here, it’s not “Blender can do this too.” It’s that finishing a focused film with strong taste beats endlessly refining a technically ambitious one. Every time.

And that makes the rest of this list make a lot more sense.

If you are experimenting with using Blender on an iPad, it’s a great way to sketch ideas and block shots early, but heavier scenes will still demand more power later in production.

#2. Plumíferos (2008)

This one doesn’t look modern. And that’s exactly why it matters.

Plumíferos was the first full-length animated feature made entirely with Blender. Not a short. Not an experiment. A real feature film, finished and released at a time when Blender was still fighting to be taken seriously at all. If you judge it purely by today’s visual standards, you’ll miss the point completely.

What Plumíferos proved was pipeline discipline. Scenes were planned because they had to be. Assets were reused because they couldn’t afford not to. Lighting was simplified because render times were already brutal by 2008 standards. None of this was stylistic minimalism. It was survival. And honestly, that constraint probably saved the project.

This is where a lot of modern Blender users get it backwards. They assume early projects were “simple” because the tools were weak. In reality, the teams were just ruthless about scope. They made decisions early and lived with them. No endless tweaking. No last-minute lighting overhauls. No “I’ll fix it in the next render.”

Does it show its age? Of course. Facial rigs are stiff in places. Shading is basic. But the film exists. That already puts it ahead of thousands of unfinished Blender features sitting on hard drives right now.

If you’re planning a long-form Blender project, Plumíferos is a quiet warning. Ambition is fine. Indecision is deadly. This film got finished because the creators respected their limits and committed early. That lesson hasn’t aged a day.

If you are exploring 2D animation in Blender, especially for storyboards or animatics, it can help you solve pacing and performance long before committing to full 3D scenes.

#3. Tears of Steel (2012)

This is where Blender stopped being boxed into animation.

Tears of Steel mixed live-action footage with heavy CGI at a time when most people still assumed Blender couldn’t handle serious VFX work. Motion tracking, compositing, environment extensions, digital characters. All done inside Blender, with the goal of stress-testing the software in real production conditions.

Some of it holds up surprisingly well. Some of it doesn’t. And that’s fine.

What still works is the integration. The way CG elements sit in real plates without constantly screaming for attention. The lighting matches more often than it misses. The camera tracking is solid enough that you stop thinking about the tech and start watching the scene. That’s the real win.

What shows its age is mostly aesthetic. Certain materials feel dated. Some animations are stiff. But those issues aren’t Blender-specific. You see the same thing in plenty of studio VFX from that era.

For Blender users, this project delivered a different kind of confidence. It showed that Blender wasn’t just for stylized worlds or contained environments. You could take it on set, bring footage back, and actually finish shots that had to match reality. That opened doors for indie filmmakers who couldn’t justify expensive VFX pipelines.

The deeper lesson here is about ambition management. Tears of Steel aimed high, but it was structured like a test lab, not a passion project spiraling out of control. Every shot had a purpose. Every technical challenge fed back into the tool itself.

If you’ve ever wanted to use Blender for live-action VFX, this film is still a reference. Not because it’s perfect, but because it proved the workflow was real.

#4. Sintel (2010)

This is the one people keep coming back to. And it’s not because of the tech.

Sintel works because it understands something a lot of Blender projects miss. Emotion carries weight when everything else gets out of the way. The story is simple, almost blunt, but every choice supports it. Camera placement is calm. Cuts are motivated. Lighting does most of the storytelling heavy lifting.

Technically, there’s nothing here that feels flashy by today’s standards. No simulation overload. No shader gymnastics. But the atmosphere still holds. Snow feels cold. Fire feels dangerous. Distance feels lonely. Those are lighting and composition decisions, not node tricks.

I’ve seen people try to recreate Sintel by copying materials or render settings, and it almost always misses the point. The look comes from planning. From knowing what time of day a scene lives in. From committing to a mood early and protecting it all the way through production.

What makes Sintel endure is focus. It never tries to be clever. It never shows off for its own sake. It just tells the story it set out to tell, cleanly and with confidence.

For Blender users, this short is still one of the best reminders that storytelling problems don’t get solved in the shader editor. They get solved on paper, before you open the file.

If you are constantly tweaking render settings to save time, it’s worth remembering that optimization helps most when scenes are designed with rendering in mind from the start.

#5. Big Buck Bunny (2008)

Comedy is brutal in 3D. Big Buck Bunny understood that early.

On the surface, this short looks playful and simple. Underneath, it’s doing a lot of heavy lifting. Exaggerated animation, clear silhouettes, readable expressions, and timing that has to land exactly right or the joke dies. There’s nowhere to hide when something isn’t funny.

From a Blender standpoint, this project pushed character animation hard for its time. Fur, skin deformation, squash and stretch, facial performance. All of it had to work together, shot after shot. And because the tone is light, mistakes stand out even more. You notice every awkward pause. Every stiff movement.

What I think made Big Buck Bunny so effective as a learning tool is that it exposed weaknesses immediately. If an animation beat was off, everyone could see it. If lighting flattened a character, the humor collapsed. That kind of feedback loop is priceless when you’re learning.

A lot of Blender artists still underestimate comedy. They chase realism or mood because those feel safer. Big Buck Bunny shows that clarity and timing are harder skills. And once you have those, everything else gets easier.

This short didn’t just entertain. It trained an entire generation of Blender animators to think about performance first. That’s a legacy that still matters.

#6. Spring (2019)

This is the short a lot of Blender users admire quietly and rarely talk about.

Spring looks simple at first glance. Soft colors. Gentle motion. Minimal dialogue. But that calm surface hides a huge amount of deliberate decision-making. Every shot is composed like a painting. Every movement feels measured. Nothing rushes.

What stands out here is restraint. The environments aren’t overloaded. Textures aren’t screaming for attention. Animation is subtle, almost reserved. That takes confidence. It’s much easier to add detail than to remove it and trust the result.

From a production standpoint, Spring is a masterclass in mood control. Lighting stays consistent across scenes. Color palettes are limited and intentional. Even small camera moves feel planned rather than reactive. This is the kind of discipline that usually comes from experience, not tutorials.

I think Spring feels even more relevant now than it did at release. There’s been a noticeable shift toward quieter, more atmospheric animation in recent years, especially in indie work. This short anticipated that trend instead of chasing spectacle.

For Blender artists, Spring is a reminder that not every project needs to shout. Sometimes the strongest choice is to lower the volume and let the audience lean in.

If you are trying to speed up your workflow, learning essential Blender shortcuts and hotkeys can make iteration feel lighter and keep momentum alive during long projects.

#7. Charge (2022)

This is what modern Blender production actually looks like.

Charge doesn’t feel like an experiment or a tech demo. It feels like a small studio project with real constraints and real deadlines. Assets are dense. Environments are complex. Lighting setups are layered. And yet the film stays readable, which is harder than it sounds.

What stands out here is how contemporary the pipeline feels. You can sense the balance between quality and practicality in every shot. Nothing feels accidental. Scenes are built to survive iteration without collapsing under their own weight. That’s a skill a lot of Blender users only learn the hard way.

There’s also a noticeable confidence in how effects are used. Explosions, debris, motion blur. They support the action instead of hijacking it. That restraint again. It keeps showing up in the strongest Blender films for a reason.

If you’ve worked on a serious Blender project recently, Charge will feel familiar. The tradeoffs. The compromises. The constant negotiation between ambition and render time. This short doesn’t pretend those problems don’t exist. It works around them.

As a reference, Charge is valuable because it reflects current reality. Not nostalgia. Not future promises. Just what Blender can do right now when it’s used with intent.

What These Blender Films All Get Right

None of these films succeeded because they pushed every Blender feature to its limit. They succeeded because they made decisions early and defended them.

Storyboards came first. Not as a formality, but as a filter. If a shot didn’t serve the story or the rhythm, it didn’t survive. Lighting wasn’t an afterthought. It was part of the narrative language, locked in before assets spiraled out of control. Scope stayed intentional. Not small, just controlled.

There’s also a shared respect for clarity. You always know where to look. You always understand what matters in the frame. That sounds obvious until you watch unfinished Blender projects that drown the viewer in detail without direction.

I’ve noticed that the best Blender films treat limitations like design constraints, not obstacles. Render time, hardware limits, team size. All of it shapes smarter creative choices instead of sabotaging them. That mindset shows up in every finished frame.

This isn’t about talent gaps. It’s about discipline. And discipline is what most personal Blender projects quietly lack.

If you are using Blender on a Chromebook, cloud-based setups become especially relevant once your scenes outgrow what local hardware can comfortably handle.

Where Most Blender Film Projects Still Break Down

This is the part nobody likes to talk about.

Most Blender film projects don’t fail because the idea was bad or the artist wasn’t skilled enough. They stall because complexity creeps in quietly and then refuses to leave. One extra prop here. One more light there. A “quick” simulation that turns into a permanent render tax.

Late in production, scenes get heavy. Renders slow down. Simple tweaks suddenly take hours to preview. That’s when motivation drops. You stop experimenting because every change feels expensive. And once iteration slows, the project starts to freeze in place.

Hardware plays a bigger role here than people admit. Not because you need the latest GPU, but because waiting kills momentum. When lighting tweaks take all night to render, you stop refining lighting. When animation previews lag, timing suffers. These are creative problems caused by technical friction.

Burnout usually follows. Not dramatic burnout. The quiet kind. You open the project less often. Weeks pass. Eventually, it becomes “that film I’ll finish someday.”

Every filmmaker on this list avoided that trap by respecting production reality early. They didn’t wait for perfect conditions. They built workflows that allowed them to keep moving. That’s the difference between a finished film and a folder full of versions.

If you are unsure which Blender render engines to use, the right choice often depends less on trends and more on how early you lock lighting and scope decisions.

Where Vagon Cloud Computer Fits Into Blender Filmmaking

At some point, Blender projects stop being limited by ideas and start being limited by hardware. Scenes get heavier. Lighting setups multiply. Simulations creep in. Even small tweaks begin to cost real time, not seconds, but hours. That’s usually when momentum starts to slip.

This is exactly where Vagon Cloud Computer makes sense for Blender filmmakers. Instead of forcing your project to fit the limits of a local machine, you move the heavy work to a high-performance cloud environment. No new hardware purchases. No underclocking your ambition just to keep renders manageable.

What matters most here isn’t raw render speed. It’s iteration speed. With Vagon, complex Blender scenes remain interactive, lighting changes are easier to test, and animation previews don’t feel like a punishment. That freedom encourages better decisions, because you can actually afford to explore them.

Vagon is especially useful for short films and feature projects where visual complexity ramps up late in production. Final lighting passes, effects-heavy sequences, dense environments. The stages where local machines often become a bottleneck. Instead of locking scenes too early or avoiding changes altogether, you stay flexible longer.

It’s not something every Blender user needs. Simple scenes and learning projects run just fine locally. But when a film’s scope grows and iteration time starts shaping creative choices, Vagon Cloud Computer stops being a convenience and becomes part of a sustainable workflow.

Final Thoughts

If there’s a common thread running through all these films, it’s not software tricks or technical flexing. It’s taste. Clear priorities. And a willingness to commit to decisions early, then live with them.

Blender is already capable. That question is settled. What still separates finished films from abandoned ones is whether the workflow supports momentum or slowly drains it. When iteration stays fast, ideas stay alive. When it doesn’t, even great concepts start to shrink.

Tools like Vagon Cloud Computer don’t replace skill or vision. They remove friction at the exact moment friction becomes dangerous. Late production. Heavy scenes. Big decisions that still need room to breathe. Used thoughtfully, that support can be the difference between polishing a film and shelving it.

The real takeaway is simple, even if it’s uncomfortable. Finishing matters more than perfection. Infrastructure should serve creativity, not quietly steer it. And the Blender films people remember are almost always the ones where someone chose progress over endless tweaking.

Blender isn’t the underdog anymore. The question now is what you do with that freedom.

FAQs

1. Can Blender really be used for professional films today?

Yes. That debate is basically over. Blender is already being used for award-winning shorts, full-length animated features, and serious VFX work. The limiting factor now isn’t the software. It’s planning, taste, and whether the production pipeline can actually support the project through the finish line.

2. Do I need a powerful local machine to make a Blender film?

Not at the beginning. Early stages like storyboarding, blocking, and rough animation run fine on modest hardware. Problems usually appear later, when scenes get dense and lighting, effects, and final renders stack up. That’s where many projects slow down or stall.

3. Why do so many Blender film projects get abandoned?

Most don’t fail because of lack of skill. They fail because iteration becomes too slow. When testing changes takes hours instead of minutes, creators stop experimenting. Momentum drops. Motivation follows. Over time, the project quietly fades out.

4. When does using Vagon Cloud Computer make sense for Blender users?

Vagon is most useful once projects move beyond simple scenes. Short films with complex lighting, feature projects, heavy environments, or late-stage polish where local machines become a bottleneck. It’s not necessary for every Blender user, but it becomes valuable when iteration speed starts shaping creative choices.

5. Will using cloud computers replace local workflows?

No. Most Blender filmmakers still use local machines for daily work. Cloud systems complement that setup. You bring in extra power when you need it, instead of forcing every project to fit your weakest hardware limit.

6. What’s the biggest lesson from successful Blender films?

Finish. Plan early. Respect constraints. And protect your ability to iterate. The films people remember aren’t the ones with the most complex shaders. They’re the ones that made clear decisions and followed through.

Get Beyond Your Computer Performance

Run applications on your cloud computer with the latest generation hardware. No more crashes or lags.

Trial includes 1 hour usage + 7 days of storage.

Get Beyond Your Computer Performance

Run applications on your cloud computer with the latest generation hardware. No more crashes or lags.

Trial includes 1 hour usage + 7 days of storage.

Get Beyond Your Computer Performance

Run applications on your cloud computer with the latest generation hardware. No more crashes or lags.

Trial includes 1 hour usage + 7 days of storage.

Get Beyond Your Computer Performance

Run applications on your cloud computer with the latest generation hardware. No more crashes or lags.

Trial includes 1 hour usage + 7 days of storage.

Get Beyond Your Computer Performance

Run applications on your cloud computer with the latest generation hardware. No more crashes or lags.

Trial includes 1 hour usage + 7 days of storage.

Ready to focus on your creativity?

Vagon gives you the ability to create & render projects, collaborate, and stream applications with the power of the best hardware.

Vagon Blog

Run heavy applications on any device with

your personal computer on the cloud.

San Francisco, California

Solutions

Vagon Teams

Vagon Streams

Use Cases

Resources

Vagon Blog

How to Create Video Proxies in Premiere Pro to Edit Faster

Top SketchUp Alternatives for 3D Modeling in 2026

How to Stop Premiere Pro from Crashing in 2026

Best PC for Blender in 2026 That Makes Blender Feel Fast

Best Laptops for Digital Art and Artists in 2026 Guide

How to Use the 3D Cursor in Blender

Top Movies Created Using Blender

Best AI Tools for Blender 3D Model Generation in 2026

How to Use DaVinci Resolve on a Low-End Computer in 2026

Vagon Blog

Run heavy applications on any device with

your personal computer on the cloud.

San Francisco, California

Solutions

Vagon Teams

Vagon Streams

Use Cases

Resources

Vagon Blog

How to Create Video Proxies in Premiere Pro to Edit Faster

Top SketchUp Alternatives for 3D Modeling in 2026

How to Stop Premiere Pro from Crashing in 2026

Best PC for Blender in 2026 That Makes Blender Feel Fast

Best Laptops for Digital Art and Artists in 2026 Guide

How to Use the 3D Cursor in Blender

Top Movies Created Using Blender

Best AI Tools for Blender 3D Model Generation in 2026

How to Use DaVinci Resolve on a Low-End Computer in 2026

Vagon Blog

Run heavy applications on any device with

your personal computer on the cloud.

San Francisco, California

Solutions

Vagon Teams

Vagon Streams

Use Cases

Resources

Vagon Blog

How to Create Video Proxies in Premiere Pro to Edit Faster

Top SketchUp Alternatives for 3D Modeling in 2026

How to Stop Premiere Pro from Crashing in 2026

Best PC for Blender in 2026 That Makes Blender Feel Fast

Best Laptops for Digital Art and Artists in 2026 Guide

How to Use the 3D Cursor in Blender

Top Movies Created Using Blender

Best AI Tools for Blender 3D Model Generation in 2026

How to Use DaVinci Resolve on a Low-End Computer in 2026

Vagon Blog

Run heavy applications on any device with

your personal computer on the cloud.

San Francisco, California

Solutions

Vagon Teams

Vagon Streams

Use Cases

Resources

Vagon Blog